\({Landslide!}\) A small earthquake has caused several rocks to tumble down the mountainside. A stone that falls from mountain that is 100 meters tall, and hits another rock halfway down (as shown in the figure.) Assume that the stone bounces off the rock with the same speed it had when initially hitting the rock, and assuming the stone was initially at rest on the mountain, calculate the horizontal distance travelled by the stone for the following scenarios:

(a) The stone hits the rock, bounces, and ricochets at a 45-degree angle.

(b) The stone hits the rock and ricochets at such an angle that it reaches the maximum possible horizontal distance.

a) Divide the problem into two stages: the first one is the stone falling from the initial height, where it’s easy to find the final speed (i.e. the initial speed of the bounce). Then, you’ll need to find the time \(t\) from the equation of motion along X, replace it in the Y equation of motion, and get a quadratic equation for the distance \(R\).

b) As you already know, it is possible to optimize a relationship between two variables using the derivative. In this case, the two variables are \(R\) and \(\theta\), and so, we can derivate the current function with respect \(\theta\).

a) For the first stage, where the stone free falls from the given height, we have:

\begin{equation*}

v_f^2=v_i^2-2g(y_f-y_i),

\end{equation*}

where we can get \(v_f\), which is:

\begin{equation*}

v_f\approx 31.3\,\text{m/s}.

\end{equation*}

For the second stage,

\begin{equation*}

x=v_x t,

\end{equation*}

where \(x = R\) and \(v_x = v \cos \theta\). For the Y motion, we have:

\begin{equation*}

\vec{y}_f=\vec{y}_i+\vec{v}_{yi}t+\frac{1}{2}\vec{a}t^2,

\end{equation*}

where \(v_{yi}= v_i \sin \theta \). By solving for \(t\) in the X equation of motion and replacing it in the previous one, we get:

\begin{equation*}

y_f=y_i+v_i\sin(\theta)\left(\frac{R}{v_i\cos(\theta)}\right)-\frac{1}{2}g\left(\frac{R}{v_0\cos(\theta)}\right)^2.

\end{equation*}

After some algebra, we can get:

\begin{equation*}

\left(\frac{1}{2} \right)R^2+\left(-\frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{2g}\right)R+\left(-\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{2g}\right)=0.

\end{equation*}

Taking just the positive answer, this yields:

\begin{equation*}

R=136.60\,\text{m}.

\end{equation*}

b) To optimize, we must take the first derivative of \(R (\theta)\) and make it equal to zero, as follows:

\begin{equation*}

\frac{dR}{d\theta}=\frac{v_0^2\cos(2\theta)}{g}+\dfrac{\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)\cos(2\theta)}{g}-\frac{2y_iv_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{g}}{\sqrt{\frac{v_0^4\sin^2(2\theta)}{4g^2}+\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(\theta))}{g}}}=0.

\end{equation*}

Defining \(\alpha = \frac{2y_i g}{\v_0^2}\), and after some algebra, we get:

\begin{equation*}

\alpha^2\tan^4(2\theta)+(\alpha^2-2\alpha)\tan^2(2\theta)-2\alpha=2\alpha(1+\tan^2(2\theta))\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}.

\end{equation*}

Solving for \(\theta\), using the explicit expression for \(\alpha\):

\begin{equation*}

\theta=\arctan\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\frac{2y_i g}{v_0^2}}}\right),

\end{equation*}

which is:

\begin{equation*}

\theta \approx 10^\circ.

\end{equation*}

This result gives us:

\begin{equation*}

R \approx 150m.

\end{equation*}

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

(a) The first part of the problem asks us to find the horizontal distance covered by the stone if it bounces at a 45-degree angle. We’ll divide the solution of the problem into two steps:

- Using a scalar equation relating the speeds, acceleration, and the distance, we’ll find the initial speed at which a rock hits the ledge located at \(y=50\,\text{m}\). We’ll assume that this is the initial speed of the subsequent parabolic motion.

- Using the speed we found before, we’ll write the trajectory equation for the parabolic motion and find the angle that maximizes the horizontal distance travelled by the rock. Once this angle is found, we can find the maximum horizontal distance \(R\).

First, we write the scalar equation relating the initial and final speeds, the acceleration, and the distance travelled in free fall, namely

\begin{equation}

\label{vf}

v_f^2=v_i^2-2g(y_f-y_i)

\end{equation}

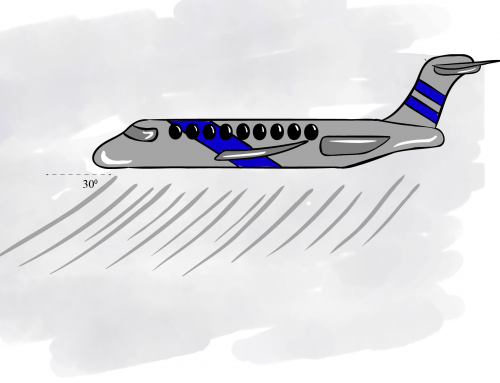

where the variables \(y_f\) and \(y_i\) represent the final and initial position respectively, \(v_f\) and \(v_i\) are the final and initial speeds, and \(g=9.8\,\text{m/s}^2\) is the gravitational acceleration of Earth. Putting our coordinate system on the ground, we find that \(y_i=100\,\text{m}\) and \(y_f=50\,\text{m}\), as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: We place the coordinate system at the base of the cliff at ground level. According to this system, the initial position of the stone is 100m, and the point at which it hits the ledge is 50m.

Using equation \eqref{vf} and the fact that the initial speed is zero, we can solve for \(v_f\) to get

\begin{equation}

v_f=\sqrt{-2g(y_f-y_i)}.

\end{equation}

Numerically, according to the system chosen, this is

\begin{equation}

v_f=\sqrt{-2(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)(50\,\text{m}-100\,\text{m})}.

\end{equation}

That is,

\begin{equation}

v_f\approx 31.3\,\text{m/s}.

\end{equation}

This will be the initial speed \(v_0\) of the parabolic motion (remember they asked us to assume that the speed of the stone just after it hits the rock is the same as the speed when it hits the rock).

We follow up with the second step of the solution: we have to write the equations for parabolic motion. Remember that a parabolic motion consists of a motion with constant vertical acceleration (along the Y axis) and a motion with constant horizontal velocity (along X). Since the stone moves in the positive X direction, the equation of motion along X for the stone is

\begin{equation}

x_f\,\hat{\textbf{i}}=x_i\,\hat{\textbf{i}}+v_{0x}t\,\hat{\textbf{i}},

\end{equation}

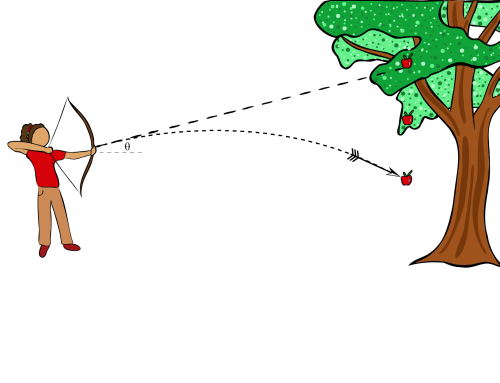

where \(v_{0x}\) is the initial speed along X, and \(x_f\) and \(x_i\) the final and initial X-positions respectively. Now, we can easily see that \(v_{0x}=v_0\cos(\theta)\), as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: After the rock hits the ledge, it has a initial velocity \(\vec{v}_i\) with components along the X and Y axis, as shown. The horizontal distance travelled from the ledge is denoted as \(d\).

Hence, we can write the previous equation as

\begin{equation}

x_f\,\hat{\textbf{i}}=x_i\,\hat{\textbf{i}}+v_0\cos(\theta)t\,\hat{\textbf{i}},

\end{equation}

or, focusing on just the magnitudes, we get

\begin{equation}

x_f=x_i+v_0\cos(\theta)t

\end{equation}

Now, from the coordinate system used, we see that \(x_i=0\) and \(x_f=R\) are the initial and final positions of the rock along the X axis, and so we get

\begin{equation}

\label{kinemx}

R=v_0\cos(\theta)t.

\end{equation}

Notice that \(R\) is actually the distance that we want to find! But to do so, we still need to find the time \(t\). so, we need more equations. Consider the motion along the Y axis. In general, this is the motion of an object with constant acceleration:

\begin{equation}

\vec{y}_f=\vec{y}_i+\vec{v}_{yi}t+\frac{1}{2}\vec{a}t^2,

\end{equation}

where \(\vec{y}_f\) and \(\vec{y}_i\) are the final and initial positions on Y, \(\vec{v}_{yi}\) is the initial velocity along Y, and \(\vec{a}\) is the acceleration (in this case, the gravitational acceleration). Now, let’s rewrite this equation using the coordinate system that we chose above. Then, the initial velocity along Y is positive according to the system, the gravitational acceleration is negative, and the initial position is positive:

\begin{equation}

y_f\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=y_i\,\hat{\textbf{j}}+v_{yi}t\,\hat{\textbf{j}}-\frac{1}{2}gt^2\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Now, from the last figure used, it is clear that \(v_{yi}=v_i\sin(\theta)\), and so we can write

\begin{equation}

y_f\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=y_i\,\hat{\textbf{j}}+v_i\sin(\theta)t\,\hat{\textbf{j}}-\frac{1}{2}gt^2\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Focusing on just the magnitudes, we have

\begin{equation}

\label{kinemy}

y_f=y_i+v_i\sin(\theta)t-\frac{1}{2}gt^2.

\end{equation}

Hence, we found a new equation where the only unknown is the time \(t\). Since we have two equations where only time is unknown, we’ll be able to find the time. Solving for \(t\) in equation \eqref{kinemx}, we have

\begin{equation}

v_0\cos(\theta) t=R.

\end{equation}

Then,

\begin{equation}

t=\frac{R}{v_0\cos(\theta)}.

\end{equation}

Using this expression for time in equation \eqref{kinemy}, we obtain

\begin{equation}

y_f=y_i+v_i\sin(\theta)\left(\frac{R}{v_i\cos(\theta)}\right)-\frac{1}{2}g\left(\frac{R}{v_0\cos(\theta)}\right)^2.

\end{equation}

But we know that \(y_f=0\,\text{m}\) (the final position along Y is the ground level, which is zero according to the coordinate system). Thus,

\begin{equation}

\label{traj0}

0=y_i+v_i\sin(\theta)\left(\frac{R}{v_i\cos(\theta)}\right)-\frac{1}{2}g\left(\frac{R}{v_0\cos(\theta)}\right)^2.

\end{equation}

To simplify further, let’s use the trigonometric identities \(\sin(\theta)/\cos(\theta)=\tan(\theta)\) and \(1/\cos^2(\theta)=\sec^2(\theta)\):

\begin{equation}

\label{traj}

0=y_i+R\tan(\theta)-\frac{1}{2}g\frac{R^2\sec^2(\theta)}{v_0^2}.

\end{equation}

Notice that we have obtained a quadratic equation for \(R\). Multiplying all terms by \(\left(-\frac{v_0^2}{g\sec^2(\theta)}\right)\), we obtain

\begin{equation}

\frac{R^2}{2}-\frac{v_0^2\tan(\theta)}{g\sec^2(\theta)}R-\frac{y_iv_0^2}{g\sec^2(\theta)}=0.

\end{equation}

Let’s use more trigonometric identities to simplify further. Let’s use \(\tan(\theta)/\sec^2(\theta)=\sin(\theta)\cos(\theta)\) and \(1/\sec^2(\theta)=\cos^2(\theta)\) to get

\begin{equation}

\frac{R^2}{2}-\frac{v_0^2\sin(\theta)\cos(\theta)}{g}R-\frac{y_iv_0^2\cos^2(\theta)}{g}=0.

\end{equation}

And once more, use these trigonometric equations: \(\sin(\theta)\cos(\theta)=\sin(2\theta)/2\) and \(\cos^2(\theta)=(1+\cos(2\theta))/2\). We finally get

\begin{equation}

\left(\frac{1}{2} \right)R^2+\left(-\frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{2g}\right)R+\left(-\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{2g}\right)=0.

\end{equation}

Notice that this is a quadratic equation for variable \(R\) of the form \(ax^2+bx+c=0\), where \(a,b,c\) are constants. The solution will be

\begin{equation}

R=\frac{-b\pm\sqrt{b^2-4ac}}{2a}.

\end{equation}

In our case, with the values of \(a,b,c\), we get

\begin{equation}

\label{req}

R=\frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{2g}\pm\sqrt{\left(\frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{2g}\right)^2-4\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(-\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{2g}\right)},

\end{equation}

which simplifies to

\begin{equation}

\label{req2} R=\frac{v_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{2g}+\sqrt{\frac{v_0^4\sin^2(2\theta)}{4g^2}+\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{g}}.

\end{equation}

Notice that we chose the positive root in order for \(R\) to be positive (the distance must be positive). Using the numerical values, including that \(\theta=45^{\circ}\), we obtain

\begin{equation}

R=\frac{(31.3\,\text{m/s})^2}{2(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)}+\sqrt{\frac{(31.3\,\text{m/s})^4\sin^2(2(45^{\circ}))}{4(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)^2}+\frac{(50\,\text{m})(31.3\,\text{m/s})^2(1+\cos(2(45^{\circ})))}{9.8\,\text{m/s}^2}}.

\end{equation}

This yields

\begin{equation}

R=136.60\,\text{m}.

\end{equation}

(b) The final part of the problem requires us to calculate the maximum horizontal distance possible by assuming that the stone bounces at an optimum angle. Since we want the maximum value for \(R\), we’ll have to take the derivative with respect to \(\theta\) and equal it to zero, namely

\begin{equation}

\frac{dR}{d\theta}=0.

\end{equation}

Calculating the derivative explicitly from \eqref{req2}, we get

\begin{equation}

\frac{dR}{d\theta}=\frac{v_0^2\cos(2\theta)}{g}+\dfrac{\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)\cos(2\theta)}{g}-\frac{2y_iv_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{g}}{\sqrt{\frac{v_0^4\sin^2(2\theta)}{4g^2}+\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(\theta))}{g}}}=0.

\end{equation}

Taking the term with the square-root to the right side, and elevating both sides to the power of 2, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\frac{v_0^4\cos^2(2\theta)}{g^2}=\frac{\left(\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)\cos(2\theta)}{2g^2}-\frac{y_iv_0^2\sin(2\theta)}{g}\right)^2}{\frac{v_0^4\sin^2(2\theta)}{4g^2}+\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{g}}.

\end{equation}

Taking common factor of the term \(\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)}{2g^2}\) in the numerator on the right, we obtain the expression

\begin{equation}

\frac{v_0^4\cos^{2}(2\theta)}{g^2}=\frac{\left(\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)}{2g^2}\right)^2\left(\cos(2\theta)-\frac{2y_i g}{v_0^2}\right)^2}{\frac{v_0^4\sin^2(2\theta)}{4g^2}+\frac{y_iv_0^2(1+\cos(2\theta))}{g}}.

\end{equation}

Factorizing the term \(\frac{v_0^4}{4g^2}\) in the denominator, we end up with

\begin{equation}

\frac{v_0^4\cos^2(2\theta)}{g^2}=\frac{\left(\frac{v_0^4\sin(2\theta)}{2g^2}\right)^2\left(\cos(\theta)-\frac{2y_i g}{v_0^2}\right)^2}{\left(\frac{v_0^4}{4g^2}\right)\left(\sin^2(2\theta)+\frac{4y_ig(1+\cos(2\theta))}{v_0^2}\right)}.

\end{equation}

Simplifying the \(\frac{v_0^4}{g^2}\) term on all the expression and defining \(\alpha=\frac{2y_ig}{v_0^2}\), we can write

\begin{equation}

\cos^2(2\theta)=\frac{\sin^2(2\theta)(\cos(\theta)-\alpha)^2}{(\sin^2(2\theta)+2\alpha(1+\cos(2\theta)))}.

\end{equation}

Dividing both sides by \(\cos^2(2\theta)\), we get

\begin{equation}

1=\frac{\tan^2(2\theta)(\cos(\theta)-\alpha)^2}{\sin^2(2\theta)+2\alpha(1+\cos(2\theta))}.

\end{equation}

Multiply everything by the term in the denominator on the right side to get

\begin{equation}

\sin^2(2\theta)+2\alpha(1+\cos(2\theta))=\tan^2(2\theta)(\cos(2\theta)-\alpha)^2.

\end{equation}

Dividing both sides again by \(\cos^2(\theta)\), we can write everything in terms of tangent and secant, explicitly

\begin{equation}

\tan^2(2\theta)+2\alpha(\sec^2(2\theta)+\sec(2\theta))=\tan^2(2\theta)(1-\alpha\sec(2\theta))^2.

\end{equation}

Now let’s use the trigonometric identity \(\sec^2(2\theta)=1+\tan^2(2\theta)\) so that we can leave all the expression in terms of \(\tan(2\theta)\):

\begin{equation}

\tan^2(2\theta)+2\alpha\left(1+\tan^2(2\theta)+\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}\right)=\tan^2(2\theta)\left(1-\alpha\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}\right)^2.

\end{equation}

Expanding all of the terms on the right and left of the expression, we get

\begin{equation}

\tan^2(2\theta)+2\alpha+2\alpha\tan^2(2\theta)+2\alpha\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}

\end{equation}

for the left-hand side and

\begin{equation}

\tan^2(2\theta)\left(1-2\alpha\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}+ \alpha^2(1+\tan^2(2\theta))\right)\end{equation}

for the right-hand side. Since these two sides are equal, we arrive at

\begin{equation}

\alpha^2\tan^4(2\theta)+(\alpha^2-2\alpha)\tan^2(2\theta)-2\alpha=2\alpha(1+\tan^2(2\theta))\sqrt{1+\tan^2(2\theta)}.

\end{equation}

Elevating both sides to the power of 2, we obtain a cubic equation for the variable \(\tan^2(\theta)\). The reader can verify that the real solution to this cubic equation is

\begin{equation}

\tan^2(2\theta)=\frac{4(1+\alpha)}{\alpha^2}.

\end{equation}

Using the double angle identity

\begin{equation}

\tan(2\theta)=\frac{2\tan(\theta)}{1-\tan^2(\theta)},

\end{equation}

we arrive at

\begin{equation}

\tan(\theta)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\alpha}}.

\end{equation}

Hence, the solution for \(\theta\) is (using the explicit expression for \(\alpha\))

\begin{equation}

\theta=\arctan\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\frac{2y_i g}{v_0^2}}}\right),

\end{equation}

which numerically is

\begin{equation}

\theta=\arctan\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+\frac{2(50\,\text{m})(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)}{(31.3\,\text{m/s}^2)}}}\right).

\end{equation}

That is,

\begin{equation}

\theta\approx 10^{\circ}.

\end{equation}

Using the numerical value for the angle \(\theta\) and the rest of the numerical values in equation \eqref{req}, we get

\begin{equation}

R\approx150\,\text{m}.

\end{equation}

Leave A Comment