\({Batter \: \: up!}\) A baseball player swings their bat toward an incoming baseball, and the ball soars off the bat at 30 m/s at an initial height of 1.5 m above the ground. The distance between the home plate and the home run zone is 122 m. Assume that the height of the barrier between the field and the home run area is 6 meters. Calculate the minimum angle necessary for a player to score a home run (assuming the angle is measured with respect to a horizontal line).

Hint: The trigonometric identity \( \sec^2 \theta = 1 + \tan^2 \theta \) may be useful, as well as the substitution \(\tan \theta = Z\).

First, try to find the time that the ball spends in the air from the motion of the ball along X. Then, use the result in the equations of motion along Y to get a quadratic equation in the \(\theta\) variable.

For an object that travels with constant speed, and remembering that \(v_x = v_i \cos \theta\), use…

\begin{equation*}

d_x=v_x t = v_i \cos \theta.

\end{equation*}

Along Y, the ball has uniform acceleration, and so the equation of motion along Y is:

\begin{equation*}

y_f = – \frac{1}{2} g t^2 + v_{i_y}t + y_i,

\end{equation*}

where \(v_{i_y} = v_i \sin \theta \). Solving for \(t\) in the first equation, and inserting the variable \(t\) in the second one, after using some algebra, we get:

\begin{equation*}

0 = – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} \tan^2 \theta + d_x \tan \theta + y_i – y_f – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2}.

\end{equation*}

This is a quadratic equation, and we can use the tip \(Z = \tan \theta\) to help solve it.

Then, to get \(\theta\) we use \( \arctan \) for both of the obtained solutions:

\begin{equation*}

\theta_1 = \arctan (0.059) = 3.38^\circ,

\end{equation*}

and

\begin{equation*}

\theta_2 = \arctan (45.86) = 88.75^\circ.

\end{equation*}

Since they asked us for the smallest angle, the answer is \( 3.38^\circ \).

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

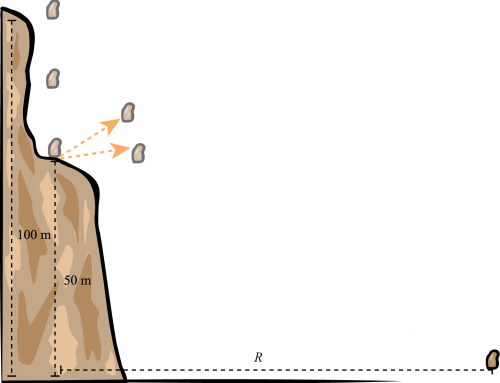

We know that the total horizontal distance that a projectile travels depends on both the horizontal speed and the flying time. Hence, in order to find the minimum angle necessary for a home run, we will need to relate this angle to both the horizontal distance and to the flying time. And notice that we need to not only make sure that the ball travels the required horizontal distance, but also check that it goes over the barrier placed between the field and the home run area. In order to relate all these variables, let’s start by placing a coordinate system on the ground (see figure 1), just below the ball at the impact.

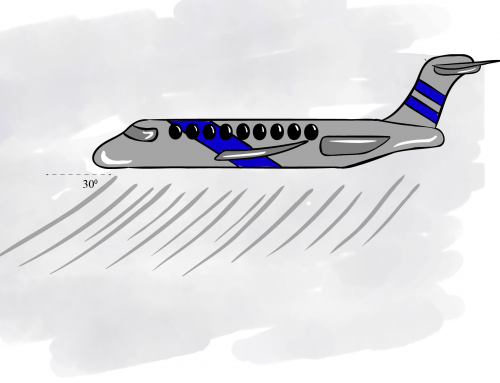

Figure 1: We place the coordinate system on the ground, just below the place where the bat hits the ball.

Now let’s consider what’s happening along X, and later we’ll consider what’s happening in Y. During a projectile motion, the horizontal speed (in this case, the velocity along X) is always constant, and so the total horizontal distance is simply given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_dvt}

d_x=v_x t,

\end{equation}

where \(v_x\) is the speed in X and \(t\) is the time. The distance we are interested in is the minimum required for a home run (they tell us it is 122 meters, but we’ll insert the values at the end). However, we don’t know the time or the velocity along X, so we need more equations. To find the velocity along X, let’s find the components of the initial velocity along X and along Y with the help of figure 2.

Figure 2: The ball’s initial velocity is shown here, along with its components along the X and Y axes. The angle \(\theta\) between the ball’s velocity and the horizontal axis is also shown.

From here, it is clear that

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_velX}

v_x = v_i \cos \theta,

\end{equation}

where \(v_i\) is the initial speed (which is known). Hence, let’s use this result in equation \eqref{Baseball_dvt} to get

\begin{equation}

d_x = (v_i \cos \theta) t.

\end{equation}

This equation relates the angle to the initial speed and to the time. But since we don’t know the time, we can’t just find the angle using the equation. So we need more equations.

We want to make sure that at the time \( t \) the ball reaches the minimum horizontal distance for a home run, its height is just enough to pass the barrier. Since the height is given by the position on Y, let’s then consider the ball’s motion on Y.

In Y, the ball has uniform acceleration (given by gravity), and so the equation of motion on Y is

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_yf}

y_f \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = – \frac{1}{2} g t^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + v_{i_y}t \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_i \, \hat{\textbf{j}},

\end{equation}

where we used the fact that the acceleration is negative on Y according to our system, the initial velocity is positive on Y, and the initial position is also positive on Y. This equation tells us the height at any time \(t\). To find the time at the moment the ball goes over the barrier, we need to use the fact that the height at that point has to be 3 meters (so that the ball can pass the barrier). But before we insert that value, let’s use the same figure as before to find the initial speed on Y.

According to the figure, that speed is given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_velY}

v_y = v_i \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Then, let’s use this result in equation \eqref{Baseball_yf} to get

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_yf2}

y_f \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = – \frac{1}{2} g t^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + (v_i \sin \theta)t \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_i \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Notice that this equation still has the time, which we don’t know, and so we can’t use it to find the angle yet. However, we can express that time in terms of the angle using equation \eqref{Baseball_velX}. In particular, if we divide both sides of equation \eqref{Baseball_velX} by \((v_i \cos \theta)\), we get

\begin{equation}

\label{Baseball_tiempo}

\frac{d_x}{v_i \cos \theta} = t.

\end{equation}

Then, using this result in equation \eqref{Baseball_yf2}, we get:

\begin{equation}

y_f \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = – \frac{1}{2} g \left( \frac{d_x}{v_i \cos \theta}\right)^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + (v_i \sin \theta) \left( \frac{d_x}{v_i \cos \theta}\right) \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_i \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Now, let’s just focus on the magnitudes and simplify each term a bit to get

\begin{equation}

y_f = – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} \frac{1}{ \cos^2 \theta} + d_x \tan \theta + y_i,

\end{equation}

where we used that \( \tan \theta = \sin \theta / \cos \theta\).

Now, use that \(1 / \cos^2 \theta = \sec^2 \theta \):

\begin{equation}

y_f = -g \frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} \sec^2 \theta + d_x \tan \theta + y_i.

\end{equation}

Now, in this equation we can use the first hint (that \( \sec^2 \theta = 1 + \tan^2 \theta \)):

\begin{equation}

y_f = – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} ( 1 + \tan^2 \theta ) + d_x \tan \theta + y_i.

\end{equation}

Notice that the hint allowed us to write the equation only in terms of one trigonometric function, namely, \( \tan \theta \). We can rearrange the terms to get

\begin{equation}

0 = – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} \tan^2 \theta + d_x \tan \theta + y_i – y_f – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2}.

\end{equation}

Let’s now use the second hint and the substitution \( \tan \theta=Z \). If we do this, we get

\begin{equation}

0 = – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} Z^2 + d_x Z + y_i – y_f – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2},

\end{equation}

which is clearly a quadratic equation of the form \(ax^2+bx+c=0\) but for \(Z\).

Here \(a\) is \(- g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2}\), \(b\) is \(d_x\) and \(c\) is \( \left( y_i – y_f – g\frac{d_x^2}{2 v_i^2} \right)\).

Finally, we can insert the numerical values:

\begin{equation}

0 = – (9.8 \text{m/s}^2)\frac{(122 \, \text{m})}{2 (30 \text{m/s})^2} Z^2 + (122 \, \text{m}) Z + (1.5 \, \text{m}) – (6 \, \text{m}) – (9.8 \text{m/s}^2)\frac{(122 \, \text{m})}{2 (30 \text{m/s})^2}.

\end{equation}

The solutions of this equation are \( Z_1 =0.059 \) and \( Z_2 = 45.86 \). Remember that \( Z = \tan \theta \), and so

\begin{equation}

(\tan \theta_1) = 0.059

\end{equation}

for the first solution, and

\begin{equation}

(\tan \theta_2) = 45.86

\end{equation}

for the second solution. To get \(\theta\), we use \( \arctan \):

\begin{equation}

\theta_1 = \arctan (0.059) = 3.38^\circ,

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

\theta_2 = \arctan (45.86) = 88.75^\circ.

\end{equation}

Since they asked us for the smallest angle, the answer is \( 3.38^\circ \).

Why is g in the denominator of the first term in equation 9?

Hi, thanks for your question! You are right that the “g” should be in the numerator. Please check back in a bit and we would have fixed the answer.

When you substitute the numbers in the last line, you forgot to square the distance (122m). The actual angle of theta is nonexistent because given the vi, the ball can never go above the wall