A typical airport runway is 2 km long. An average passenger aircraft takes off at a minimum speed of 322 km/h.

(a) Calculate the minimum acceleration the turbines have to provide to ensure a successful take off.

(b) During landing, how much time would it take for the plane to stop if it touches the ground at 200 km/h and uses the entire runway? What is the acceleration in this case?

(a) Use an equation that relates the following variables: acceleration, distance, initial speed and final speed. Also, make sure to use SI units.

(b) Take into account that the final speed is zero. Then, use an equation that relates the acceleration found in (a) to the time and initial speed.

(a) In order to find the minimum acceleration the turbines have to provide for the plane to take off, we need to relate that acceleration to the runway length’s and to the minimum speed required for taking off. This is easy if we use the following equation:

\begin{equation*}

v_f^2 – v_i^2 = 2 a d.

\end{equation*}

Using the numerical values we get:

\begin{equation*}

a = 25921 \, \text{km/h}^2.

\end{equation*}

(b) Now consider the case where the airplane is landing. In order to find the time it takes for the airplane to completely stop, we can use the fact that during a motion with constant acceleration, the final velocity is given by:

\begin{equation*}

\vec{v}_f = \vec{a}t + \vec{v}_i,

\end{equation*}

and the magnitude of the acceleration is:

\begin{equation*}

\frac{v_f^2 – v_i^2}{2d} = a.

\end{equation*}

By combining the last two equations and using the numerical values we get:

\begin{equation}

t_b = 0.02 \, \text{h}.

\end{equation}

And the acceleration is:

\begin{equation*}

\vec{a} = -10000 \, \text{km/h}^2 \, \hat{\textbf{i}},

\end{equation*}

where (\(10000 \, \text{km/h}^2\)) is the magnitude and the \(-\hat{\textbf{i}}\) indicates the direction.

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

(a) In order to find the minimum acceleration the turbines have to provide for the plane to take off, we need to relate that acceleration to the runway length’s and to the minimum speed required for taking off. This is easy if we use the equation

\begin{equation}

\label{Plane_velAlCuadradoConA}

v_f^2 – v_i^2 = 2 a d,

\end{equation}

where \(v_f\) is the final speed, \(v_i\) the initial speed, \(a\) the (magnitude’s) acceleration and \(d\) the distance. If we divide by \(2d\) everywhere, we get

\begin{equation}

\label{Plane_aceleracion}

\frac{v_f^2 – v_i^2}{2d} = a.

\end{equation}

Before inserting the numerical values, notice that we are interested in the minimum acceleration. This means that we are assuming that the airplane uses the entire runway for take off. Of course, if the airplane were to use only a fraction of the runway, then it would require greater acceleration to reach the take off speed in such a reduced distance (which means we would not be dealing with the minimum acceleration). This is why we should use \(d = 2 \, \text{km}\) in this equation if we are to find the minimum acceleration. Let’s also use the fact that the initial speed is zero and that the take off speed is 322 k/h:

\begin{equation}

\frac{(322 \, \text{km/h})^2 – (0)^2}{2(2 \, \text{km})} = a,

\end{equation}

to get

\begin{equation}

a = 25921 \, \text{km/h}^2.

\end{equation}

It is worth mentioning that we could have solved this problem if we had begun with equation \( \vec{x}_f = \vec{x}_i + \vec{v}_i t + \frac{1}{2} \vec{a} t^2 \) instead. But in that case, we would have had to find the time \(t\) using equation \( \vec{v}_f = \vec{a}t + \vec{v}_i \). Of course, the result would have been same; however, we would have needed to use more equations. In general, when we have a kinematics problem where we do not need to find the time and we have the distance and the speeds, it is very convenient to use equation\eqref{Plane_velAlCuadradoConA}).

(b) Now consider the case where the airplane is landing. In order to find the time it takes for the airplane to completely stop, we can use the fact that during a motion with constant acceleration (as in this case), the final velocity is given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Plane_velocidadVector}

\vec{v}_f = \vec{a}t + \vec{v}_i.

\end{equation}

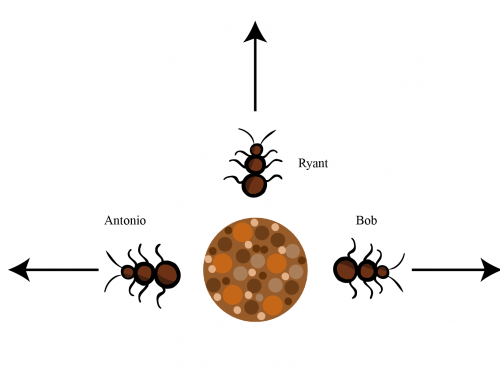

In order to apply this equation to this case, let’s choose a coordinate system where the origin is just at the beginning of landing and the the X axis points in the direction of motion (see figure 1):

Figure 1: We place the coordinate system at the plane’s initial position.

Notice that according to this system, the initial velocity is positive. Furthermore, we want to find the time that the airplane takes to break, and so the final velocity must be zero at that time (when the airplane has completely stopped and has no velocity). Since it is breaking, the acceleration is also negative. So equation \eqref{Plane_velocidadVector} becomes

\begin{equation}

0 \, \hat{\textbf{i}} = v_i \, \hat{\textbf{i}} – a t_b \, \hat{\textbf{i}},

\end{equation}

where \(t_b\) is the time it takes the plane to break. If we focus on the magnitudes only and rearrange the terms, we get

\begin{equation}

\label{Plane_VelInicial}

at_b = v_i.

\end{equation}

Now, we do not know neither \(a\) nor \(t\), so we need to find more equations. To get \(a\) we can use equation \eqref{Plane_aceleracion} again because we know the distance (it is the same runaway again) and the final and initial speeds. Insert that equation in \eqref{Plane_VelInicial} to get

\begin{equation}

\left( \frac{v_f^2 – v_i^2}{2d} \right) t_b = v_i

\end{equation}

However, we need to be careful about the signs. Notice that in \((v_f^2-v_i^2)\) is negative because \(v_f\) is zero. This means that the acceleration in equation \eqref{Plane_aceleracion} will be negative as well. That is fine, but then we have to be careful about equation \eqref{Plane_VelInicial} because there we also used the fact that the acceleration was negative. In other words, the \(a\) in equation \eqref{Plane_VelInicial} already took into account the sign of the acceleration (recall that we used (\(- a t_b \, \hat{\textbf{i}}\)), and \(a\) is just the magnitude. So, when we use \eqref{Plane_aceleracion}, we have to put a negative sign to ensure that we get the magnitude of \(a\). Hence, we should actually write

\begin{equation}

-\left( \frac{v_f^2 – v_i^2}{2d} \right) t_b = v_i.

\end{equation}

Now, let’s divide everything by \(-\left( \frac{v_f^2 – v_i^2}{2d} \right)\):

\begin{equation}

t_b = \frac{2dv_i}{v_i^2 – v_f^2}.

\end{equation}

And finally, insert the numerical values here (use that the final speed is zero).

\begin{equation}

t_b = \frac{2 (2 \, \text{km})(200 \, \text{km/h})}{\left( (200 \, \text{km/h})^2 – (0)^2\right)}

\end{equation}

to get

\begin{equation}

t_b = 0.02 \, \text{h}.

\end{equation}

Finally, we need to find the acceleration in this second case. Let’s use equation \eqref{Plane_aceleracion} again. If we use the numerical values there, and that \(v_f\) is zero, we get

\begin{equation}

a = \frac{(0)^2 – (200 \, \text{km/h})^2}{2((2 \, \text{km}))},

\end{equation}

and then

\begin{equation}

a = -10000 \, \text{km/h}^2.

\end{equation}

Notice that the sign is negative, which indicates that the acceleration is negative in X, as we expected. So, a more precise way of writing the acceleration is as

\begin{equation}

\vec{a} = -10000 \, \text{km/h}^2 \, \hat{\textbf{i}},

\end{equation}

where (\(10000 \, \text{km/h}^2\)) is the magnitude and the \(-\hat{\textbf{i}}\) indicates the direction.

Wonderful, congratulations. Thank you