The Cali Tower is a skyscraper in Colombia that is 183 meters tall. A tennis ball is released from the roof of Cali Tower, and four seconds later, a second tennis ball is released from the point. (Assume air resistance is negligible, and the tennis ball’s mechanical energy is conserved when it bounces on the ground.)

(a) Once the second tennis ball is released, how much time does it take for the two tennis balls to collide?

(b) At what height will the two tennis balls meet?

(a) Notice that the total time that passes between the moment the first ball is released and the moment the balls meet can be written in terms of two other time intervals that you need to find. And notice that this total time is different from the total time that passes between the moment the second ball is released up until the moment the balls meet again. Also, if the balls meet, their final positions must be the same. Finally, notice that both balls fall with constant acceleration.

(b) Use the time found for the second ball to find the height.

(a) Define \(t_g\) and \(t_b\) as the time it takes the first ball to reach the ground and bounces to meet the second ball, respectively. Let’s call this total time ‘\(t_{m1}\)’:

\begin{equation*}

t_{m1} = t_g + t_b.

\end{equation*}

Define also \(t_d\) the delayed time and \(t_{m2}\) the time for the second ball to meet the first ball:

\begin{equation*}

t_{m2} = t_{m1} – t_d = t_g + t_b – t_d.

\end{equation*}

The motion for an object with constant gravitational acceleration is described by the equation:

\begin{equation*}

\vec{y}_f = \frac{1}{2} \vec{a} t^2 + \vec{v}_i t + \vec{y}_i.

\end{equation*}

Using the corresponding values, solving for \(t_g\) we have:

\begin{equation*}

t_g = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}}.

\end{equation*}

To find \(t_b\) we need to find the initial speed of the bouncing part and replace it in the equation of motion described earlier. By relating the final’s positions of the balls as:

\begin{equation*}

\vec{y}_{f1}(t_b)=\vec{y}_{f2}(t_b),

\end{equation*}

and using the time \(t_{m2}\) in terms of \(t_g, t_b\) and \(t_d\), after a lot of algebra we can get:

\begin{equation*}

t_b = \frac{1}{2} t_d,

\end{equation*}

which lead us to:

\begin{equation*}

t_{m2} = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} – \frac{1}{2} t_d,

\end{equation*}

or with numerical values:

\begin{equation*}

t_{m2} = 4.11 \, \text{s}.

\end{equation*}

(b) Finding the height at which the balls meet is very easy once we know the time at which this happens. Using the time in the equation of motion we get:

\begin{equation*}

y_{f1} = 100.18 \, \text{m}.

\end{equation*}

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

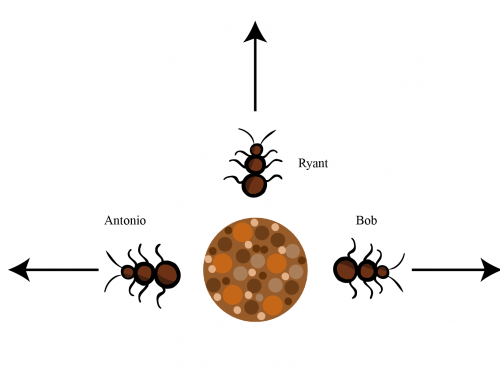

(a) We need to find the time between the moment the second ball is released and the moment the two balls meet. Of course, the balls will only meet after the first tennis ball bounces on the ground and starts going up. Please bear in mind that is important to distinguish between the motion of the first ball when going down, its motion after it bounces on the ground, and the motion of the second ball going down. It is also very important to distinguish between the different time intervals in question. Indeed, there are four different time intervals that we need to distinguish:

(1) One time interval, call it \(t_g\), corresponds to the time that passes between the moment the first ball is released, and the moment that ball touches the ground.

(2) A different time interval, call it \(t_b\), corresponds to the time that passes between the moment the first ball touches the ground and the moment it meets the second ball (they meet when the first ball is going up after bouncing and the second ball is going down).

(3) Clearly, if we add \(t_g\) and \(t_b\), we get the total time that passes between the moment the first ball is released, and the moment the balls meet. Let’s call this total time ‘\(t_{m1}\)’:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoTotalBola1}

t_{m1} = t_g + t_b.

\end{equation}

(4) A fourth time interval to take into account corresponds to the time that we actually need to find: the total time that passes between the moment the second ball is released up until the moment the balls meet again. This time, let’s call it `\(t_{m2}\)’, is different from \(t_{m1}\) (explained above) because the second ball is released four seconds after the first one. For example, if the total time that passes from the moment the first ball is released up until the moment the balls meet is ten seconds (this is \(t_{m1}\)), then the total time that passes from the moment the \textit{second} ball is released up until the moment the balls meet is only six seconds (this is \(t_{m2}\)). More precisely, these times are related via the following equation:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoTotalBola2}

t_{m2} = t_{m1} – t_d,

\end{equation}

where \(t_d\) is the delay between the two balls (we know that it is four seconds, but we will use the numerical value at the end).

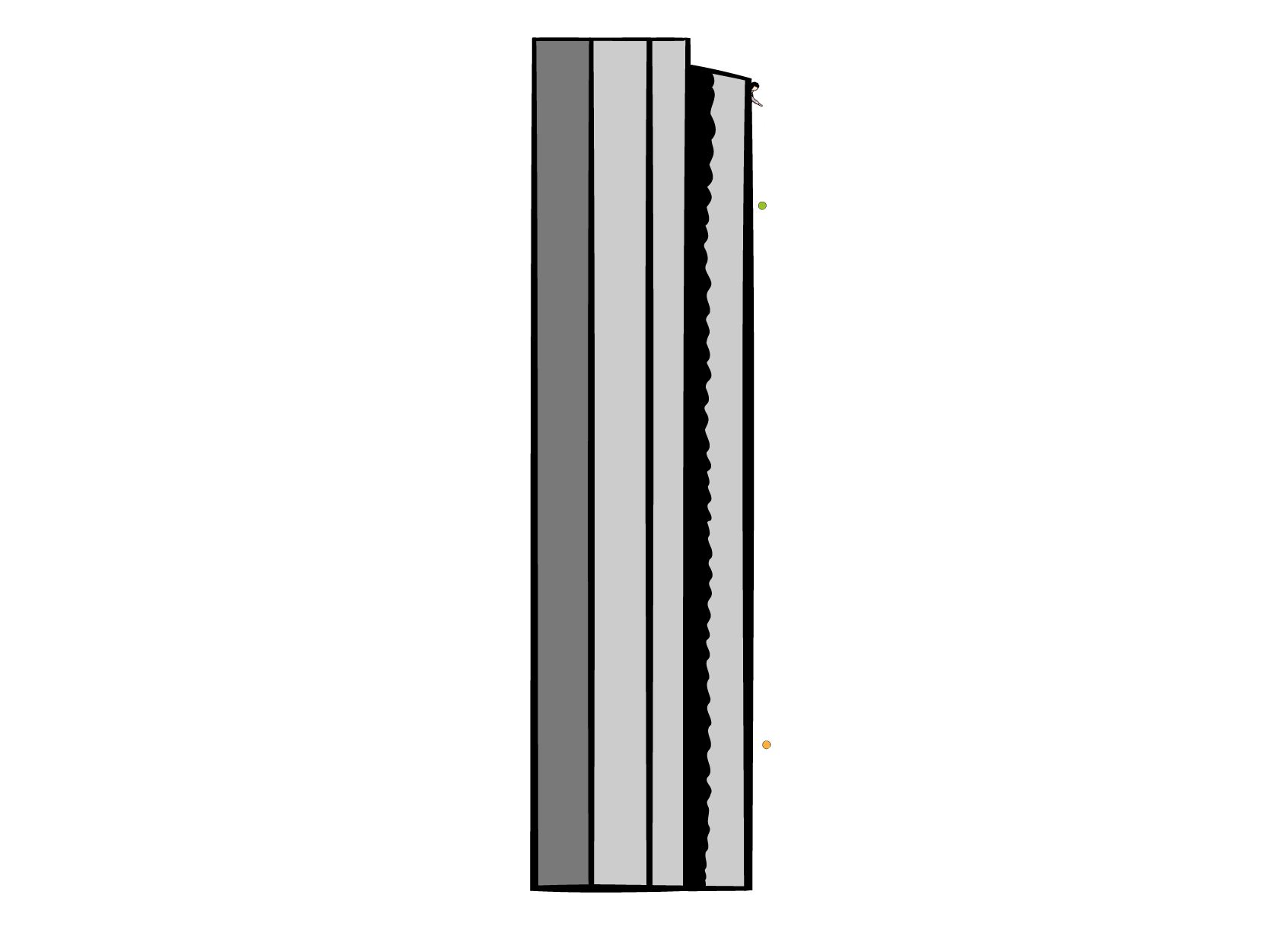

It might be helpful to create a drawing illustrating the different times in question (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The three figures show the position of the balls for different times. On the left, we show the position at time \(t_g\). On the center figure, we show the position at time \(t_b\). On the figure on the right, we show the position at time \(t_{m1}\) for the first tennis ball and \(t_{m2}\) for the second tennis ball.

Let’s use equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoTotalBola1} in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoTotalBola2}:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoM2}

t_{m2} = t_g + t_b – t_d.

\end{equation}

According to this equation, to find \(t_{m2}\) we need to find \(t_g\) and \(t_b\) (we know \(t_d\)). So, let’s focus on \(t_g\) first.

The time it takes for the first ball to touch the ground can be found from its equation of motion. Since we want \(t_g\) first, we will first focus on the equation of motion for the interval between the moment the ball is released and the moment the ball touches the ground. To write the equation of motion, let’s start by choosing a coordinate system. We will place the origin on the ground, exactly at the point where the ball will bounce.

Figure 2: We place the coordinate system at the base of the Cali tower.

Since the ball is in free fall, its motion in Y is that of an object with constant gravitational acceleration. In general, the equation of motion for an object with constant acceleration is

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_posicionVectores}

\vec{y}_f = \frac{1}{2} \vec{a} t^2 + \vec{v}_i t + \vec{y}_i,

\end{equation}

where \(\vec{y}_f\) is the final position, \(\vec{y}_i\) is the initial position, \(\vec{v}_i\) is the initial speed, \(a\) is the acceleration and \(t\) is the time.

In the present circumstances, according to our coordinate system, the initial position is positive in Y (and it is 183 meters), the initial velocity is zero (because the object is released, not thrown), the acceleration is the gravitational one which is negative, and the final position is zero because we are focusing on the time it takes for the ball to touch the ground (this time is \(t_g\)). Hence, we get

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_caso1}

0 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g t_g^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + (0) t_g \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_i \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

If we focus on the magnitudes only, and move \(-\frac{1}{2} g t_g^2\) to the other side, we get

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} g t_g^2 = y_i.

\end{equation}

Let’s divide everything by \(\frac{1}{2}g\) to get

\begin{equation}

t_g^2 = \frac{2 y_i}{g}.

\end{equation}

Hence, taking the square root, we find

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoTG}

t_g = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}}.

\end{equation}

We can then plug in this result in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoM2} to get

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoM2ConTM1}

t_{m2} = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} + t_b – t_d.

\end{equation}

The only unknown variable now is \(t_b\), so let’s focus our effort on finding it.

Recall that \(t_b\) is the time that passes measured from the moment the first ball touches the ground and the moment when both balls meet. This means that their positions at time \(t_b\) are the same (they meet then):

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_velocidades}

\vec{y}_{f1}(t_b)=\vec{y}_{f2}(t_b),

\end{equation}

where \(\vec{y}_{f1}(t_b)\) is the position of the first ball at time \(t_b\), and \(\vec{y}_{f2}(t_b)\) the position of the second ball at that same time. These positions are given by the equations of motion, so let’s consider these now.

Previously we found the equation of motion for the first ball (see equation \eqref{KinBuilding_caso1}), but that equation was only for the moments between when the ball was released up until the moment it touched the ground. Now we will consider the equation of motion for the interval between the moment the ball bounces on the ground and the moment it meets the other ball. Of course, it is still a motion with constant acceleration given by gravity (and it is still negative, according to our system), and so equation \eqref{KinBuilding_posicionVectores} still applies. But now a couple of things are different. First, the initial position is the floor, and so it is zero according to our coordinate system. Second, the initial speed is no longer zero, since the ball is bouncing off the ground with some initial positive velocity (we do not know this velocity yet). And third, the time that we care about is \(t_b\). Hence, the equation of motion for this ball in the current situation is

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_caso2}

y_{f1} \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + v_i t_b \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + 0 \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

The next step is to find \(v_i\). They tell us that no energy is lost while the ball bounces on the ground. This means that whatever kinetic energy the ball had when touching the ground for the first time, it must still have that same kinetic energy when `taking off’ the ground while bouncing. That is, \(\frac{1}{2}mv_g^2 = \frac{1}{2}mv_i^2 \), where \(v_g\) is the speed just when reaching the floor and \(v_i\) is the speed when leaving the floor while bouncing. Since the ball’s mass is obviously the same, this equation shows that \(v_g=v_i\). And so the question is: How do we find \(v_g\) (which is the speed when reaching the floor)?

\(v_g\) is easy to find given that we know the acceleration and the time. In particular, for an object moving with constant acceleration, we know that

\begin{equation}

\vec{v}_f = \vec{a} t + \vec{v}_i.

\end{equation}

In our case, we want the velocity when touching the ground knowing that the ball is released (so the initial velocity is zero). The time is \(t_g\), and the acceleration is negative and given by \(g\). So we get

\begin{equation}

\vec{v}_g = – g t_g \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + 0 \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Notice that the sign indicates that the velocity is negative, since at this moment the ball is falling. But we only need the speed (the magnitude), which is

\begin{equation}

v_g = g t_g.

\end{equation}

Now, let’s use the fact that \(t_b\) is given by equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoTG}:

\begin{equation}

v_g = g \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}}.

\end{equation}

Since this is the same as the speed when leaving the ground (because the energy is conserved), then we can use this result in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_caso2}:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_caso22}

y_{f1} \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + \left( g \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} \right) t_b \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Now, let’s insert this result in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_velocidades}:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_velocidadesIgualadas}

-\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + \left( g \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} \right) t_b \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = y_{f2} \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

The next step is to consider the equation of motion of the second ball. The second ball also moves with constant acceleration (given by gravity), and so a lot of what we already said about the first ball applies to the second ball. For example, the initial speed is zero because the ball is released, the initial height is the same as the initial height for the first ball, namely, \( y_{i} \, \hat{\textbf{j}}\) (which is \(183\) meters), and gravity’s acceleration is negative according to our system. Hence, the equation of motion for the second ball would be

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_y2}

y_{f2} \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g {t^*}^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + v_i {t^*} \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_{i}\, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Despite the similarities, there is an important difference when comparing it to equation \eqref{KinBuilding_caso2}: the times for these equations are not the same. The reason is that \(t_b\) is the time it takes for the first ball to meet the second ball from the moment the first ball bounces. But \(t^*\) is the time it takes for the second ball to meet the first ball from the moment the second ball is released. Recall that this is precisely what we called \(t_{m2}\) earlier. So in order to continue, we should make sure that the equations of motion are given in terms of the same time variable (it would not make much sense to compare the final positions of these balls if these positions are given in terms of different time variables).

Thankfully, we already know how to relate \(t_b\) and \(t_{m2}\) using equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoM2}. To repeat,

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tiempoM2ParaRelacionarTiempos}

t_{m2} = t_g + t_b – t_d.

\end{equation}

So let’s use this result in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_y2}:

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_y22}

y_{f2} \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g (t_g + t_b – t_d)^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + (0) (t_g + t_b – t_d) \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_{i} \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Now that this equation of motion is in terms of \(t_b\), (\(t_g\) and \(t_d\) are already known), we can use it in equation \eqref{KinBuilding_velocidadesIgualadas}. We get

\begin{equation}

-\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + \sqrt{2 g y_i} t_b \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = -\frac{1}{2} g (t_g + t_b – t_d)^2 \, \hat{\textbf{j}} + y_{i} \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

We need to find \(t_b\) from this equation. First, move all the terms to the left side and focus only on the magnitudes to get

\begin{equation}

-\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 + \sqrt{2 g y_i} t_b + \frac{1}{2} g (t_g + t_b – t_d)^2 – y_{i} = 0

\end{equation}

We can now explicitly operate the term \((t_g + t_b – t_d)^2\):

\begin{equation}

-\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 + \sqrt{2 g y_i} t_b + \frac{1}{2} g (t_b^2 + 2 t_b (t_g – t_d) + (t_g – t_d)^2) – y_{i} = 0.

\end{equation}

Then, if we distribute the third term (counted from the left), we get:

\begin{equation}

-\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 + \sqrt{2 g y_i} t_b + \frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 + g t_b (t_g – t_d) + \frac{1}{2}g(t_g – t_d)^2 – y_{i} = 0.

\end{equation}

Now we see that the terms \(\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2\) can be canceled. Let’s move all the terms that do not involve \(t_b\) to the right side:

\begin{equation}

\sqrt{2 g y_i} t_b + g t_b (t_g – t_d) = y_i – \frac{1}{2}g(t_g – t_d)^2.

\end{equation}

On the left side, \(t_b\) can be factorized,

\begin{equation}

t_b ( \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) ) = y_i – \frac{1}{2}g(t_g – t_d)^2,

\end{equation}

and then we can divide everything by \( ( \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) ) \) to get

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tBSinSimplificar}

t_b = \frac{y_i – \frac{1}{2}g(t_g – t_d)^2}{ \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) }.

\end{equation}

The reader can now insert the numerical values in this equation if she wishes. However, we will simplify further (because why not?). Let’s multiply everything by \(2g/2g\) (this is like multiplying by one so the equation will not be changed). The reason we’re doing this is that it will help us simplify the algebra, as we show now.

\begin{equation}

t_b = \left( \frac{2g}{2g} \right) \frac{y_i – \frac{1}{2}g(t_g – t_d)^2}{ \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) }.

\end{equation}

Now we can distribute the \(2g\) factor in the numerator

\begin{equation}

t_b = \left( \frac{1}{2g} \right) \frac{2gy_i – g^2(t_g – t_d)^2}{ \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) }.

\end{equation}

Notice that the numerator is now a difference of two squared terms, and so we can use \(a^2-b^2=(a+b)(a-b)\). In our case, \(2gy_i=a^2\) and \(g^2(t_g – t_d)^2=b^2\). If we use this, we get

\begin{equation}

t_b = \left( \frac{1}{2g} \right) \frac{[\sqrt{2gy_i} – g(t_g – t_d)][\sqrt{2gy_i} + g(t_g – t_d)]}{ \sqrt{2 g y_i} + g (t_g – t_d) }.

\end{equation}

The second factor in the numerator cancels with the denominator, and we get

\begin{equation}

t_b = \left( \frac{1}{2g} \right) \left[\sqrt{2gy_i} – g(t_g – t_d) \right].

\end{equation}

Then we can distribute the other \(2g\) factor:

\begin{equation}

t_b = \frac{\sqrt{2gy_i}}{2g} – \frac{g}{2g}(t_g – t_d).

\end{equation}

Here \(g\) can be canceled and \( \frac{\sqrt{2g}}{2g} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2g}} \) (because \( \frac{\sqrt{2g}}{2g} =\frac{(2g)^{0.5}}{2g}=(2g)^{0.5-1}\), which is the same as \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2g}}\)). Hence,

\begin{equation}

t_b = \sqrt{\frac{y_i}{2g}} – \frac{1}{2}(t_g – t_d).

\end{equation}

Now, let’s use equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoTG}:

\begin{equation}

t_b = \sqrt{\frac{y_i}{2g}} – \frac{1}{2}\left(\sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} – t_d\right).

\end{equation}

By distributing the 1/2 factor and by inserting it inside the square root (to do so, we have to insert it as 1/4), we get

\begin{equation}

t_b = \sqrt{\frac{y_i}{2g}} – \sqrt{\frac{y_i}{2g}} + \frac{1}{2} t_d.

\end{equation}

So, finally, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\label{KinBuilding_tBConSimplificar}

t_b = \frac{1}{2} t_d.

\end{equation}

It took a lot of work, but notice that this is a much simpler equation than the one obtained before (\eqref{KinBuilding_tBSinSimplificar}). Sometimes a little more algebra can be gratifying.

Now that we found \(t_b\) and \(t_g\) (see equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoTG}), we can finally find \(t_{m2}\) using equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tiempoM2ParaRelacionarTiempos}. The result is

\begin{equation}

t_{m2} = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} + \frac{1}{2} t_d – t_d.

\end{equation}

If we add the last two terms, we get

\begin{equation}

t_{m2} = \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} – \frac{1}{2} t_d.

\end{equation}

Finally, we can insert here the numerical values:

\begin{equation}

t_{m2} = \sqrt{\frac{2 (183 \, \text{m})}{(9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2)}} – \frac{1}{2} (4 \, \text{s}).

\end{equation}

The final answer is

\begin{equation}

t_{m2} = 4.11 \, \text{s}.

\end{equation}

(b) Finding the height at which the balls meet is very easy once we know the time at which this happens. Let’s use the equation obtained previously (equation \eqref{KinBuilding_caso22}), and let’s focus only on the magnitudes:

\begin{equation}

y_{f1} = -\frac{1}{2} g t_b^2 + \left( g \sqrt{\frac{2 y_i}{g}} \right) t_b .

\end{equation}

Now, using \(t_b\) from equation \eqref{KinBuilding_tBConSimplificar} and inserting the \(g\) term inside the square root (we need to insert it as \(g^2)\)), we get

\begin{equation}

y_{f1} = -\frac{1}{2} g \left( \frac{1}{2} t_d \right)^2 + \sqrt{2 g y_i} \left( \frac{1}{2} t_d \right)

\end{equation}

Finally, using the numerical values, we get

\begin{equation}

y_{f1} = -\frac{1}{2} (9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2) \left( \frac{1}{2} (4 \, \text{s}) \right)^2 + \sqrt{2 (9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2) (183 \, \text{m})} \left( \frac{1}{2} (4 \, \text{s}) \right).

\end{equation}

The result is

\begin{equation}

y_{f1} = 100.18 \, \text{m}.

\end{equation}

So the balls meet at an approximate height of 100 meters.

Leave A Comment