A rocket made from soda and scotch mints is launched from the ground. The initial mass of the full rocket is \(3\,\text{kg}\). If the soda sprays out of the rocket at a speed (relative to the rocket) of \(14\,\text{m/s}\) at a constant rate of \(2\,\text{kg/s}\), and the rockets trajectory is straight upwards:

a) Find the velocity as a function of time for the rocket.

b) Make a graph of velocity as a function of time.

a) Use the conservation of linear momentum as a differential form. Then the velocities can be related to the difference between them. Using Newton’s second law, the velocity \(v_y\) can be found by integrating over a time \(t\), and the rate of the change of mass can be related with the mass at time \(t\).

b) Graph the equation obtained as a function of \(t\). The graph may not be entirely familiar from calculus courses.

a) Newton’s second law can be written as

\begin{equation*}

\sum \vec{F}=\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt},

\end{equation*}

where

\begin{equation*}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\Delta \vec{p}}{\Delta t}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)}{\Delta t}.

\end{equation*}

The difference of the momentum is

\begin{equation*}

\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)=\left(m-\Delta m\right)(\vec{v}+\Delta \vec{v})+\Delta m \vec{u}-m\vec{v}.

\end{equation*}

Dividing by \(\Delta t\) on both sides and taking the limit, we get

\begin{equation*}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\left( m\frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}+\frac{\Delta m}{\Delta t}\left(\vec{u}-\vec{v}-\Delta \vec{v}\right)\right).

\end{equation*}

The relative velocity \(\vec{u}_{\text{rel}} = \vec{u} – \vec{v}\). Since the only force acting is the weight, it can be written as

\begin{equation*}

-mg =m\frac{dv_y}{dt}+\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y}.

\end{equation*}

Then, for the velocity \(v_y\), we get:

\begin{equation*}

v_{y} =-\int_{0}^{t}\left(\frac{1}{m}\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y}+g\right)\,dt.

\end{equation*}

After performing the integral, we get:

\begin{equation*}

v_{y} =u_{\text{rel}y}\ln\left(\frac{m_t}{m_0}\right)-gt.

\end{equation*}

Since \(m_t = m_0 + \frac{dm}{dt} \), the velocity can be written as

\begin{equation*}

v_{y}=u_{\text{rel}y}\ln\left(\frac{m_0+\frac{dm}{dt}t}{m_0}\right)-gt,

\end{equation*}

which, using numerical values, we have

\begin{equation*}

v_{y} = (-1\,\text{m/s})\ln\left(\frac{3\,\text{kg}-(0.5\,\text{kg/s})t}{3\,\text{kg}}\right)-(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)t.

\end{equation*}

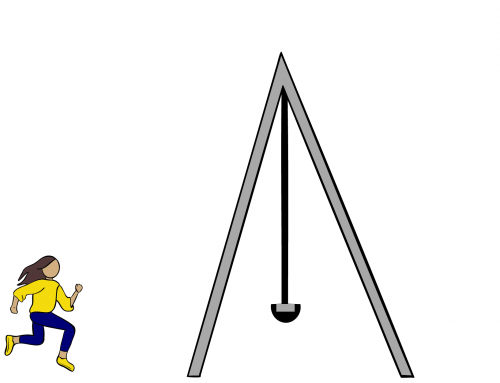

b) A graph depicting velocity \(v_{y}\) vs time \(t\) is depicted below:

Graph of the velocity \(v_x\) vs \(t\).

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

a) In order to solve this problem, we must address Newton’s second law from the point of view of linear momentum. It’s clear that as the rocket ascends, its mass will decrease, so we can’t use the usual form of Newton’s law.

For this reason, we’ll write Newton’s second law as

\begin{equation}\label{n2l}

\sum \vec{F}=\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt},

\end{equation}

where \(\sum\vec{F}\) is the sum of all external forces and \(\vec{p}\) is the linear momentum, where in equation \eqref{n2l}, we see its derivative with respect to time. Let’s write the derivative with respect to time as the limit:

\begin{equation}\label{derivative}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\Delta \vec{p}}{\Delta t}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)}{\Delta t},

\end{equation}

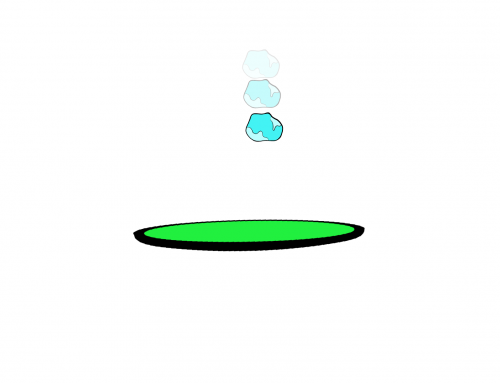

where \(\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)\) is the linear momentum in the time \(t+\Delta t\), and \(\vec{p}(t)\) is the linear momentum at time \(t\) (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Change of the momentum for each object.

From figure 1, we can see the states of the rocket: at time \(t\), it has a mass \(m\) and velocity \(\vec{v}\), while at time \(t+\Delta t\), its mass is reduced by a small amount \(\Delta m\) of soda, which leaves the rocket at a velocity \(\vec{u}\) with respect to the ground. The velocity of the rocket thus changes by a small amount \(\Delta \vec{v}\).

We can then write the linear momentum at time \(t\) as

\begin{equation}\label{pt}

\vec{p}(t)=m\vec{v},

\end{equation}

while the linear momentum at time \(t+\Delta t\) is

\begin{equation}\label{pt2}

\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)=\left(m-\Delta m\right)(\vec{v}+\Delta \vec{v})+\Delta m \vec{u}.

\end{equation}

The difference of linear momentum in the time interval \(\Delta t\) is, using the result from \eqref{pt} and \eqref{pt2},

\begin{equation}

\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)=\left(m-\Delta m\right)(\vec{v}+\Delta \vec{v})+\Delta m \vec{u}-m\vec{v},

\end{equation}

where we can expand the terms in parenthesis to get

\begin{equation}

\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)=m\vec{v}+m\Delta \vec{v}-\Delta m\vec{v}-\Delta m\Delta \vec{v}+\Delta m\vec{u}-m\vec{v},

\end{equation}

which simplifies to

\begin{equation}\label{dp}

\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)= m\Delta \vec{v}+\Delta m\left(\vec{u}-\vec{v}-\Delta \vec{v}\right).

\end{equation}

Dividing by \(\Delta t\) on both sides of the expression \eqref{dp}, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\frac{\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)}{\Delta t}= m\frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}+\frac{\Delta m}{\Delta t}\left(\vec{u}-\vec{v}-\Delta \vec{v}\right).

\end{equation}

Taking the limit as \(\Delta t\to 0\) on both sides, we obtain the left-hand-side of equation \eqref{n2l}. Explicitly,

\begin{equation}\label{dpmom}

\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\vec{p}(t+\Delta t)-\vec{p}(t)}{\Delta t}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\left( m\frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}+\frac{\Delta m}{\Delta t}\left(\vec{u}-\vec{v}-\Delta \vec{v}\right)\right).

\end{equation}

On the left-hand-side of \eqref{dpmom}, we obtain, according to the derivative definition \eqref{derivative}, the derivative of linear momentum,

\begin{equation}\label{dpmom2}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\left( m\frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}+\frac{\Delta m}{\Delta t}\left(\vec{u}-\vec{v}-\Delta \vec{v}\right)\right).

\end{equation}

In order to take the limit on the right side of equation \eqref{dpmom2}, we must can use similar definitions for the following derivatives

\begin{equation}\label{lim1}

\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\Delta \vec{v}}{\Delta t}=\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\label{lim2}

\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\frac{\Delta m}{\Delta t}=\frac{dm}{dt},

\end{equation}

and know that

\begin{equation}\label{lim3}

\lim_{\Delta t\to 0}\Delta \vec{v}=0.

\end{equation}

Taking the limit on the right side of equation \eqref{dpmom2}, using equations \eqref{lim1}, \eqref{lim2} and \eqref{lim3}, we have

\begin{equation}\label{dpdt}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=m\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}+\frac{dm}{dt}(\vec{u}-\vec{v}).

\end{equation}

Notice that the first term on the right side of equation \eqref{dpdt} is the usual mass times acceleration and that the second term includes the change of mass in time \(\frac{dm}{dt}\). The difference \(\vec{u}-\vec{v}\) can be interpreted as the velocity at which the mass comes out of the rocket relative to it. Explicitly,

\begin{equation}\label{rel}

\vec{u}_{\text{rel}}=\vec{u}-\vec{v}.

\end{equation}

Equation \eqref{dpdt} becomes, using equation \eqref{rel}:

\begin{equation}

\frac{d\vec{p}}{dt}=m\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}+\frac{dm}{dt}\vec{u}_{\text{rel}},

\end{equation}

and Newton’s second law \eqref{n2l} can be written as

\begin{equation}\label{newton}

\sum \vec{F}=m\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}+\frac{dm}{dt}\vec{u}_{\text{rel}}.

\end{equation}

The only force exerted on the rocket is its weight \(\vec{W}\), so, equation \eqref{newton} becomes

\begin{equation}\label{newton2}

\vec{W}=m\frac{d\vec{v}}{dt}+\frac{dm}{dt}\vec{u}_{\text{rel}}.

\end{equation}

Since the rocket moves along the Y-axis, we’ll write equation \eqref{newton2} along the Y-axis. Namely,

\begin{equation}\label{newton3}

-mg\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=m\frac{dv_y}{dt}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}+\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}},

\end{equation}

where we’ve used the fact that the weight’s magnitude is \(mg\) directed downwards; \(v_{y}\) is the component of the velocity along the Y-axis and \(u_{\text{rel}y}\) is the component of the relative velocity at which soda comes out of the rocket along the Y-axis. Dividing both sides of equation \eqref{newton3} by \(m\) and rearranging the terms, we obtain

\begin{equation}\label{newton4}

\frac{dv_y}{dt}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=-\left(\frac{1}{m}\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y}+g\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Keep in mind that in this problem the mass is not a constant, therefore the rate \(\frac{dm}{dt}=-2\,\text{kg/s}\) is negative because the rocket loses mass. Also notice that \(u_{\text{rel}y}=-14\,\text{m/s}\) with the negative sign because, relative to the rocket, the soda that’s pouring out has a downward velocity. To find the velocity \(v_{y}\) in terms of time, we must integrate equation \eqref{newton4} with respect to time. Namely,

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(\int_{0}^{t}\frac{dv_y}{dt}\,dt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}},

\end{equation}

which, according to equation \eqref{newton4}, is

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(-\int_{0}^{t}\left(\frac{1}{m}\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y}+g\right)\,dt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Dividing the integral above with respect to time for each term, we have

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(-\int_{0}^{t}\frac{1}{m}\frac{dm}{dt}u_{\text{rel}y} \,dt-\int_{0}^{t}g\,dt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Changing the first integral to be over mass \(m\) rather than time \(t\), we obtain

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(u_{\text{rel}y}\int_{m_0}^{m_t}\frac{dm}{m}-g\int_{0}^{t}\,dt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}},

\end{equation}

where \(m_0\) and \(m_t\) are the masses at time \(0\) and \(t\) respectively. Notice that we took \(u_{\text{rel}y}\) and \(g\) out of the integrals because they are constant. Performing the integral, we obtain

\begin{equation}\label{vyfinal}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(u_{\text{rel}y}\ln\left(\frac{m_t}{m_0}\right)-gt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

Since the mass decreases at a constant rate \(\frac{dm}{dt}\), we can write an expression for the mass in terms of time as a linear equation

\begin{equation}\label{mt}

m_t=m_0+\frac{dm}{dt}t.

\end{equation}

Using the result of \eqref{mt} on the expression found in \eqref{vyfinal}, we get

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left(u_{\text{rel}y}\ln\left(\frac{m_0+\frac{dm}{dt}t}{m_0}\right)-gt\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}},

\end{equation}

which is the expression for velocity as a function of time that we wanted to find. Using the numerical values, we have

\begin{equation}

v_{y}\,\hat{\textbf{j}}=\left((-1\,\text{m/s})\ln\left(\frac{3\,\text{kg}-(0.5\,\text{kg/s})t}{3\,\text{kg}}\right)-(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2)t\right)\,\hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

b) A graph of velocity \(v_{y}\) vs time \(t\) can be seen in figure 2.

Figure 2: Graph of the velocity \(v_x\) vs \(t\).

where we can see that at time \(t=1.5\text{s}\) the mass of the remaining soda is zero, and so the rocket starts to free fall.

Leave A Comment