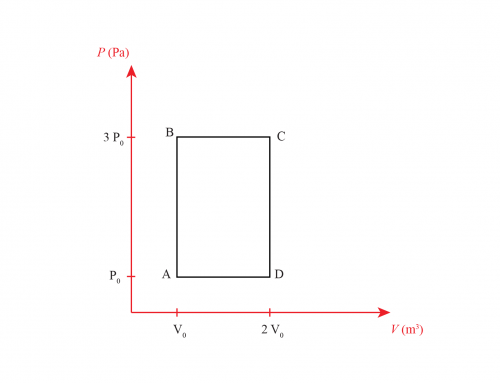

A \(n\) mol monoatomic gas follows the cycle shown in the figure.

If the process from \(a\) to \(b\) is isothermic, find the efficiency of the heat engine that follows the cycle.

Use the definition of work and the first law of thermodynamics to get the work and heat, respectively. Then use the efficiency equation. Try to put everything in terms of the pressure and the volume by the ideal gas law.

The thermodynamic efficiency \(\eta\), can be calculated as:

\begin{equation*}

\eta=1-\left|\frac{Q_{\text{out}}}{Q_{\text{in}}}\right|,

\end{equation*}

The work done is:

\begin{equation*}

W = \int_{V_i}^{V_f} P dV.

\end{equation*}

Since \(P V = nRT\), then:

Process A \(\rightarrow\) B.

\begin{equation*}

W_{A \rightarrow B} = P_a V_a \ln \left( \frac{V_b}{V_a} \right).

\end{equation*}

The first law of thermodynamics states:

\begin{equation*}

\Delta U = Q – W,

\end{equation*}

and since \( \Delta U = 0\) for an isothermic process, then \(Q=W\). Using the corresponding values in terms of \(P\) and \(V\) we get:

\begin{equation*}

Q_{C \rightarrow A} = -2 PV \ln (2).

\end{equation*}

Process B \(\rightarrow\) C.

\begin{equation*}

Q_{B \rightarrow C} = n C_p (T_c – T_b),

\end{equation*}

where using that \(T = PV / nR\), and the equivalency with \(P\) and \(V\), after some algebra we get:

\begin{equation*}

Q_{B \rightarrow C} = \frac{C_p}{R} 2 PV.

\end{equation*}

Process C \(\rightarrow\) A.

\begin{equation*}

Q_{C \rightarrow A} = n C_V (T_a – T_c),

\end{equation*}

where using that \(T = PV / nR\), and the equivalency with \(P\) and \(V\), after some algebra we get:

\begin{equation*}

Q_{C \rightarrow A} = -\frac{C_V}{R} 2 PV.

\end{equation*}

Then, \(Q_{\text{in}} = Q_{B \rightarrow C} \), so:

\begin{equation*}

Q_{\text{in}} = \frac{C_p}{R} 2 PV,

\end{equation*}

And for \(Q_{\text{in}} = Q_{A \rightarrow B} + Q_{C \rightarrow A} \), so:

\begin{equation*}

Q_{\text{out}} = -2PV \left( \ln (2) + \frac{C_V}{R} \right).

\end{equation*}

Then, the efficiency is:

\begin{equation*}

\eta=1-\dfrac{\frac{3}{2}}{\ln(2)+\frac{5}{2}},

\end{equation*}

or:

\begin{equation*}

\eta \approx 0.53.

\end{equation*}

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

We need to find the efficiency of the heat engine shown in the problem’s figure. To approach this type of problem, we begin by taking note of the variables of state given explicitly by the problem (including the graph) and the relations we can establish between these variables through the knowledge of the thermodynamic processes. Then, we can use the definition of efficiency for a thermodynamic process, the ideal gas law, and the state variables to simplify further our answer.

Let’s begin by identifying the pressure \(P\) and the volume \(V\) for each point of our cycle. According to the graph we have \(P_a=P\), \(P_b=2P\), \(P_c=2P\); \(V_a=2V\), \(V_b=V\) and \(V_c=2V\). Now we identify the type of processes in our thermodynamic cycle: from \(a \to b\) is isothermal, as the problem states, from \(b \to c\) is isobaric, since pressure does not change and from \(c \to a\) is isochoric because volume does not change. From these relations, we can write the following expressions

\begin{equation}

T_a=T_b,

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

P_b=P_c,

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

V_c=V_a.

\end{equation}

Now, we turn our attention to calculating the thermodynamic efficiency of the cycle \(\eta\), using the definition

\begin{equation}

\label{eff}

\eta=1-\left|\frac{Q_{\text{out}}}{Q_{\text{in}}}\right|,

\end{equation}

where \(Q_\text{out}\) is the sum of all the heat that leave the system and \(Q_\text{in}\) is the sum of all the heat that enters the system.

Now, let’s identify in which processes heat leaves or enters the system. In the process \(a\to b\), we have an isothermal compression, which means the work done by the gas is negative (because it decreases its volume). We can use the first law of thermodynamics

\begin{equation}

\label{firstlaw}

\Delta U=Q-W,

\end{equation}

where \(\Delta U\) is the change of the internal energy of the system, \(Q\) is the heat and \(W\) the work done by the gas; to find a relation between the heat and the work done on this process. The internal energy is a quantity that depends on the number of moles, the degrees of freedom of the gas, and its temperature. In an isothermal process, the internal energy does not change, thus \(\Delta U_{a\to b}=0\). Using this result in equation \eqref{firstlaw}, we can write

\begin{equation}

\Delta U_{a\to b}= Q_{a\to b}-W_{a\to b},

\end{equation}

and simplifying

\begin{equation}

0=Q_{a\to b}-W_{a\to b},

\end{equation}

or equivalently

\begin{equation}

\label{QWab}

Q_{a\to b}=W_{a\to b}.

\end{equation}

As we said before, the work done by the gas is negative in the process \(a\to b\), so the heat is also negative, which means that is leaving the system. We can calculate its value explicitly if we calculate the work \(W_{a\to b}\). For a general process \(x\to y\) the work can be calculate through the following expression

\begin{equation}

\label{work}

W_{x\to y}=\int_x^y P\,dV.

\end{equation}

Then, using \eqref{work} for the process \(a\to b\), we have

\begin{equation}

\label{workab}

W_{a\to b}=\int_a^b P\,dV.

\end{equation}

To perform the integral, we must express the pressure \(P\) in terms of the volume, this can be easily done if we use the ideal gas law

\begin{equation}

\label{idealgas}

PV=nRT,

\end{equation}

where \(n\) is the number of moles, \(R\) is the ideal gas constant and \(T\) is the absolute temperature of the gas. Solving for \(P\) in equation \eqref{idealgas}, we have

\begin{equation}

\label{idealgasp}

P=\frac{nRT}{V}.

\end{equation}

Using equation \eqref{idealgasp} into equation \eqref{workab}, we have

\begin{equation}

\label{workab2}

W_{a\to b}=\int_a^b\frac{nRT}{V}\,dV.

\end{equation}

Note that in the process \(a\to b\), the term \(nRT\) is constant, so we can take it out of the integral of equation \eqref{workab2}; then,

\begin{equation}

\label{workab3}

W_{a\to b}=nRT_{a\to b}\int_{a}^b\frac{dV}{V},

\end{equation}

where we have made explicit that the temperature is the one from the process \(a\to b\) by writing \(T_{a \to b}\). We can then make the integral to obtain

\begin{equation}

W_{a\to b}=nRT_{a\to b}\left[\ln(V)\right]_{a}^b=nRT_{a\to b}\left(\ln(V_b)-\ln(V_a)\right),

\end{equation}

which simplifies to

\begin{equation}

\label{workab4}

W_{a\to b}=nRT_{a\to b}\ln\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right).

\end{equation}

Moreover, we can change the term \(nRT_{a\to b}\) using equation \eqref{idealgas} to either one of the two expressions

\begin{equation}

nRT_{a\to b}=P_a V_a,

\end{equation}

or

\begin{equation}

nRT_{a\to b}=P_b V_b.

\end{equation}

We choose the former expression to replace in equation \eqref{workab4} and get

\begin{equation}

W_{a\to b}=P_a V_a\ln\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right).

\end{equation}

Coming back to equation \eqref{QWab}, we obtain an expression for the heat \(Q_{a\to b}\) as follows

\begin{equation}

\label{Qab}

Q_{a\to b}=P_a V_a\ln\left(\frac{V_b}{V_a}\right),

\end{equation}

which simplifies further by using the values of \(P_a\), \(V_a\) and \(V_b\) to

\begin{equation}

\label{Qabf}

Q_{a\to b}=(P)(2V)\ln\left(\frac{V}{2V}\right)=2PV\ln\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=-2PV\ln(2).

\end{equation}

Where we have used logarithm properties in the last line \(\ln\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=-\ln(2)\).

Now, let’s concentrate on the process \(b\to c\), in which the heat can be readily calculated as

\begin{equation}

\label{Qbc}

Q_{b\to c}=nC_p\Delta T,

\end{equation}

where \(C_p\) is the heat capacity of the gas at constant pressure and \(\Delta T\) is the change of temperature, that is \(\Delta T=T_c-T_b\). Using the ideal gas law given in equation \eqref{idealgas} and solving for the temperature, we have

\begin{equation}

\label{idealgast}

T=\frac{PV}{nR}.

\end{equation}

Then we can write the temperatures \(T_b\) and \(T_c\) in terms of known variables as

\begin{equation}

\label{Tb}

T_b=\frac{P_b V_b}{nR},

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

\label{Tc}

T_c=\frac{P_c V_c}{nR}.

\end{equation}

Using the expressions of equations \eqref{Tb} and \eqref{Tc} into \eqref{Qbc}, we obtain the following expression

\begin{equation}

Q_{b\to c}= n C_p\left(T_c-T_b\right),

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

Q_{b\to c}=n C_p\left(\frac{P_cV_c}{nR}-\frac{P_bV_c}{nR}\right).

\end{equation}

Taking the term\( \frac{1}{nR}\) as a common factor, we have

\begin{equation}

Q_{b\to c}=\frac{nC_p}{nR}\left(P_cV_c-P_bV_b\right)=\frac{C_p}{R}\left(P_cV_c-P_bV_b\right).

\end{equation}

Notice that \(P_cV_c=(2P)(2V)=4PV\) and \(P_bV_b=(2P)(V)=2PV\), so we can simplify the expression above to

\begin{equation}

\label{Qbcf}

Q_{b\to c}=\frac{C_p}{R}(4PV-2PV)=\frac{C_p}{R}2PV,

\end{equation}

a quantity that is positive, since all variables in it are positive; thus, in the process \(b\to c\) heat enters the system.

Finally, let’s examine the process \(c\to a\), where the heat can be calculated according to

\begin{equation}

\label{Qca}

Q_{c\to a}=nC_V\Delta T=nC_V(T_a-T_c),

\end{equation}

where \(C_V\) is the heat capacity of the gas at constant volume. We can use equation \eqref{idealgast} to write the temperature \(T_a\) as

\begin{equation}

\label{Ta}

T_a=\frac{P_aV_a}{nR}.

\end{equation}

Putting together the expressions of equations \eqref{Tc} and \eqref{Ta} into equation \eqref{Qca} we get

\begin{equation}

Q_{c\to a}=nC_V\left(\frac{P_aV_a}{nR}-\frac{P_cV_c}{nR}\right),

\end{equation}

which can be simplified further if we take the common factor \(\frac{1}{nR}\) to obtain

\begin{equation}

Q_{c\to a}=\frac{C_V}{R}(P_aV_a-P_cV_c).

\end{equation}

Replacing the values given by the problem, we arrive at

\begin{equation}

Q_{c\to a}=\frac{C_V}{R}((P)(2V)-(2P)(2V))=\frac{C_V}{R}(2PV-4PV),

\end{equation}

which simplifies to

\begin{equation}

\label{Qcaf}

Q_{c\to a}=-\frac{C_V}{R}(2PV),

\end{equation}

a quantity that is negative. Hence, in the process \(c\to a\) heat leaves the system.

Now that we know in which processes heat enters or leaves the system, we can then say that

\begin{equation}

Q_{\text{in}}=Q_{b\to c},

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

Q_{\text{out}}=Q_{a\to b}+Q_{c\to a}.

\end{equation}

If we put the explicit expressions for each heat given by equations \eqref{Qabf}, \eqref{Qbcf} and \eqref{Qcaf} in the expressions above, we will find that

\begin{equation}

\label{qin}

Q_{\text{in}}=\frac{C_p}{R}2PV,

\end{equation}

and

\begin{equation}

\label{qout}

Q_{\text{out}}=-2PV\ln(2)-\frac{C_V}{R}2PV.

\end{equation}

The latter expression in equation \eqref{qout} can be further simplified if we take the common factor \(-2PV\). Explicitly,

\begin{equation}

\label{qout2}

Q_{\text{out}}=-2PV\left(\ln(2)+\frac{C_V}{R}\right).

\end{equation}

Coming back to the original question abut the efficiency of the cycle, we can use the results of equations \eqref{qin} and \eqref{qout2} into \eqref{eff} to write down the following expression for the efficiency

\begin{equation}

\eta=1-\left|\dfrac{\frac{C_p}{R}2PV}{-2PV\left(\ln(2)+\frac{C_V}{R}\right)}\right|.

\end{equation}

Cancelling out the \(2PV\) and taking the absolute value (eliminating the minus sign of the denominator), we have

\begin{equation}

\label{eff2}

\eta=1-\dfrac{\frac{C_p}{R}}{\ln(2)+\frac{C_V}{R}}.

\end{equation}

To get an idea for the numerical efficiency of this cycle, let’s consider an ideal monoatomic gas. The values of the heat capacities at constant volume and at constant pressure are \(C_V=\frac{3}{2}R\) and \(C_p=\frac{5}{2}R\), respectively. We can use this in equation \eqref{eff2}

\begin{equation}

\eta=1-\dfrac{\frac{3}{2}}{\ln(2)+\frac{5}{2}}\approx 0.53.

\end{equation}

Which means that from the heat that enters the cycle, \(53\%\) of it can be transformed into work.

Leave A Comment