Two vehicles of the same mass collide at a traffic light, as shown in the figure. Both cars have the same mass; each car is 1 metric tonne (1,000 kg.) A police officer calculates that, after the collision, the vehicles slid together for a distance of \(20 \, \text{m}\). According to a video recording of the accident provided by a local convenience store, the red vehicle had an initial speed of \(12 \, \text{m/s}\). Calculate the coefficient of kinetic friction between the red car and the pavement. (Assume that the mechanical energy transferred from the red car to thermal energy due to the damage during the collision is \(70 \, \text{KJ}\).)

Use the Work-Energy Theorem to relate the velocities and the work done by the friction to get the coefficient of kinetic friction.

The Work-Energy Theorem (\(W_{Tot} = \Delta K \)) can be written as:

\begin{equation*}

W_{f_r} + W_c= K_f – K_i,

\end{equation*}

where \(W_{f_r} = -f_r d \). Since the car is moving horizontally, Newton’s Second Law in the \({y-}\)direction can be written as:

\begin{equation*}

N-mg=0.

\end{equation*}

Substituting the force due to friction into the first equation, and working with the normal force recently found, the kinetic energy, and finally solving for \(\mu\), we get:

\begin{equation*}

\mu = \frac{W_c + \frac{1}{2} m v_i^2}{mgd},

\end{equation*}

which, with numerical values, we get:

\begin{equation}

\mu = 0.37.

\end{equation}

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

In order to find the coefficient of dynamic friction between the red car and the pavement, we need to relate the friction to the other variables, such as the initial speed and the 20 meters the car slides before stopping. A way of relating these variables is by using the work-energy theorem, which states that the change in kinetic energy equals the total work of all the forces acting on the object. That is

\begin{equation}

\label{CarCrash_trabajoenergia}

\Delta K = W_{Tot}\;,

\end{equation}

where \(\Delta K\) means \(K_f-K_i\) (the change in kinetic energy). Now, let’s focus on \(W_{Tot}\). How do we find the total work? The total work includes the work done by the friction between the tires and the pavement. But it also includes the work done by any forces involved during the collision between the cars (notice that neither the weight nor the normal force produced by the pavement does any work since these forces are perpendicular to the direction of motion and so the dot product between them and the displacement will be zero). So equation \eqref{CarCrash_trabajoenergia} can be written as

\begin{equation}

\label{CarCrash_trabajos}

K_f – K_i = W_{f_r} + W_c,

\end{equation}

where \(W_{f_r}\) is the work by friction and \(W_c\) is the work of the forces that appear during the collision. Thankfully, we already know how much energy is lost during the collision (it is \(70 \, \text{kJ}\)), which means we already know \(W_c\). But we won’t use this number just yet.

For the work of friction, we need to calculate

\begin{equation}

W_{f_r} = \vec{f_r} \cdot \vec{d},

\end{equation}

where \(\vec{f_r}\) is the friction force and \(\vec{d}\) is the displacement during which the force acted (and ‘\(\cdot\)’ is the dot product). We can write explicitly the dot product in this manner:

\begin{equation}

\label{CarCrash_trabajoFriccion}

W_{f_r} = f_r d \cos \theta,

\end{equation}

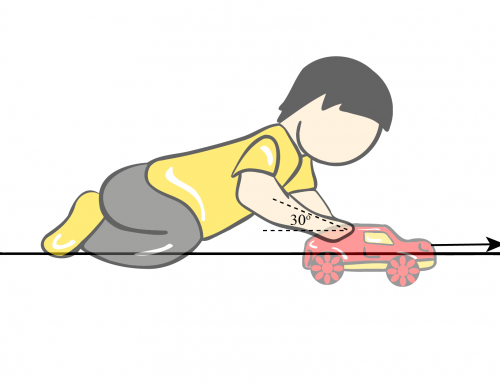

where \(\theta\) is the angle between the force vector and the displacement vector (and \(f_r\) and \(d\) are the magnitudes of the friction force and the displacement, respectively). To continue, it is helpful to make a diagram where the friction force and the displacement are delineated, so that we know which angle to use in equation \eqref{CarCrash_trabajoFriccion}. We will also choose a coordinate system where the X axis points in the direction of motion (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Friction force \(f_r\) and displacement \(d\) for the cars. The coordinate system is chosen with the X axis pointing in the direction of the displacement.

As one can appreciate from this figure, the friction is perfectly anti-parallel to the displacement, and so the angle between the vectors is \(\pi\). Since \( \cos \pi = – 1\), then we get

\begin{equation}

\label{CarCrash_trabajoConFriccionReemplazar}

W_{f_r} = – f_r d.

\end{equation}

Now, we know \(d\) (it is 20 meters), but we do not know yet \(f_r\). Recall that the force of kinetic friction is always given by

\begin{equation}

\label{CarCrash_friccion}

f_r = \mu N,

\end{equation}

where \(N\) is the normal force exerted by the surface (in this case the road) and \(\mu\), is the coefficient of kinetic friction that what we want to find. So the next step is to find \(N\).

If we use the coordinate system indicated above, we only find two forces on Y, namely, the weight and the normal force, as indicated in figure 2.

Figure 2: This is just a partial free-body diagram for the cars showing three forces: the contact force with the ground \(N\), the weight \(W\) and the friction force \(fr\) (we ignore the forces produced by the blue car because we do not need them for what follows)

Newton’s second Law in Y gives:

\begin{equation}

N \, \hat{\textbf{j}} – W \, \hat{\textbf{j}} = m a_y \, \hat{\textbf{j}}.

\end{equation}

But the car is not moving along Y, so \(a_y\) is zero. Also, \(W = mg\), and so we get

\begin{equation}

N \, \hat{\textbf{j}} – mg \, \hat{\textbf{j}}= 0 \, \hat{\textbf{j}}

\end{equation}

If we move \(mg\) to the other side and focus on the magnitudes only, we obtain

\begin{equation}

N = mg.

\end{equation}

So let’s use this in equation \eqref{CarCrash_friccion}:

\begin{equation}

f_r = \mu (mg).

\end{equation}

And now use this in \eqref{CarCrash_trabajoConFriccionReemplazar} to get

\begin{equation}

W_{f_r} = – (\mu mg) d.

\end{equation}

Now use this result in equation \eqref{CarCrash_trabajos} to get

\begin{equation}

K_f – K_i = (- \mu mgd) + W_c.

\end{equation}

Since the car stops at the end, the final kinetic energy is zero. On the other hand, the initial kinetic energy is simply \(\frac{1}{2}m v_i^2 \), where \(v_i\) is the initial speed, that is known. So we get

\begin{equation}

(0)- \left( \frac{1}{2} m v_i^2 \right) = – \mu mgd + W_c.

\end{equation}

If we move \(-\mu mgd\) and \( \left( \frac{1}{2} m v_i^2 \right) \) each to the other side, we get

\begin{equation}

\mu mgd = W_c + \frac{1}{2} m v_i^2.

\end{equation}

Now divide by (\(mgd\)) to finally get

\begin{equation}

\mu = \frac{W_c + \frac{1}{2} m v_i^2}{mgd}.

\end{equation}

All we need to do now is insert the numerical values. But we need to be careful about \(Wc\). The energy dissipated during the collision is \(70 \, \text{kJ}\), which means we have to use -\(70 \, \text{kJ}\) here (with a negative sign). Recall that \(W_c\) is the work done by all the forces appearing during the collision. These forces reduce the energy of the car (they dissipate that energy into the environment), this means that the work they do is negative (if it were positive, they would be giving energy to the car, making it move faster!). With that clarification in mind, we then get

\begin{equation}

\mu = \frac{(-70 \, \text{kJ}) + \frac{1}{2} (1000 \, \text{kg}) (12 \, \text{m/s})^2}{(1000 \, \text{kg}) (9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2) (20 \, \text{m})}.

\end{equation}

And the result is

\begin{equation}

\mu = 0.37.

\end{equation}

Leave A Comment