A teenager is playing on an old pinball machine at an arcade. They pull the plunger, thereby fully contracting a 10 cm spring and launching an 80 g metal ball upward on the slanted board, that barely makes it to the top. The board of the pinball machine is 1 meter x 0.5 meters, and is slanted at a 6.5º angle relative to the ground. Assume that, when the spring is fully contracted, the ball is 1 cm above the bottom edge of the table, as indicated in the figure. Calculate the spring constant and the speed of the ball right after leaving the spring.

Apply Conservation of Energy, and write the ball’s height as a function of the angle. To solve for velocity, apply Conservation of Energy, and write the contracted distance as a function of the height and the angle.

Based on geometric principles, the height of the ball is related to the distance and the angle as:

\begin{equation*}

\sin \theta = \frac{h_i}{d_i},

\end{equation*}

where \(h_1\) is the height of the ball measured from the origin to the equilibrium point of the spring, \( d_1\) is the diagonal distance between those two points, and the variables \(h_2\) and \(d_2\) are measured from the origin to the maximum displacement of the ball.

Applying Conservation of Energy, we can write:

\begin{equation*}

\frac{1}{2} kx^2 + mgd_1 \sin \theta= mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation*}

Solving for \(k\), we get:

\begin{equation*}

k = \frac{2mg \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1)}{x^2},

\end{equation*}

which, with numerical values, yields:

\begin{equation*}

k = 17.57 \, \text{N/m}.

\end{equation*}

To solve for velocity, it is useful to ponder the moment the ball leaves the spring. Using Conservation of Energy again, we can write:

\begin{equation*}

mg(d_1 + x) \sin \theta + \frac{1}{2} mv^2 = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation*}

Solving for \(v\), we get:

\begin{equation*}

v = \sqrt{2 g \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1 – x)},

\end{equation*}

which, with numerical values, yields:

\begin{equation*}

v = 1.4 \, \text{m/s}.

\end{equation*}

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

In order to find the spring constant, we need to relate it to the contraction of the spring, as well as to the initial and maximum height the ball reaches over the board. To do this, we can use the conservation of energy. Why? Because the elastic energy of the spring (which depends on the spring constant and its contraction) is transformed into gravitational potential energy of the ball (that depends on the ball’s mass and the height).

To use conservation of energy, we need to start by identifying the system. In this case, the system whose energy is conserved consists of the spring and the ball (because the spring transfers all of its elastic energy to the ball’s mechanical energy). Notice that the ball’s energy by itself is not conserved because the spring is increasing the ball’s energy when it pushes it up, and the spring’s energy by itself is not conserved because the spring loses its energy while it transfers it to the ball. So, we need to focus on the mechanical energy of the ball-spring system.

Conservation of energy means that

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_conservacion}

E_{m_1} = E_{m_2},

\end{equation}

where \(E_{m_1}\) is the mechanical energy at some time 1, and \(E_{m_2}\) at another time 2. Let’s choose time 1 to be the moment where the spring is completely contracted and time 2 to be the moment where the ball reaches the highest point of the board. When the spring is completely contracted, it has elastic energy given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_energiaElastica}

U_\ell = \frac{1}{2} k x^2,

\end{equation}

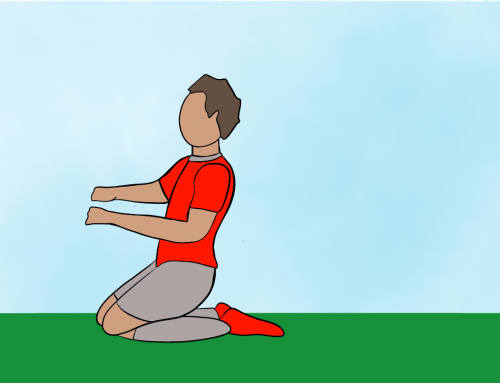

where \(k\) is the spring constant and \(x\) is the contraction (we know the contraction but not \(k\)). Now, when the spring is completely contracted, the ball is not moving and so it has no kinetic energy (\( \frac{1}{2}mv^2 =0\) since \(v=0\)). But the ball will have gravitational potential energy depending on the reference point we use to measure the height. Let’s choose the bottom edge of the board to be the reference point, and call \(h_1\) to be the height at that point, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1: Coordinate system placed on the edge of the pinball board. Notice that the initial height of the ball with respect to the Y axis is \(h_1\).

So the initial mechanical energy for the ball is just

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_energiaPotencial}

U_{g_1} = mg h_1.

\end{equation}

Since we know the inclination of the board, and we know the distance between the ball at the lowest point and the bottom edge, we can easily find \(h_1\) by paying attention to the triangle found in figure 2.

Figure 2: Initial position of the ball. The distance along the board from the origin is denoted by \(d_1\).

From the drawing, we see that

\begin{equation}

h_1 = d_1 \sin \theta,

\end{equation}

where \(d_1= 1 \, \text{cm}\) and \(\theta\) is 6.5 degrees, but we will only replace the numerical values at the end. Now use this result in equation \eqref{Pinball_energiaPotencial} to get

\begin{equation}

U_{g_1} = mg d_1 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Taking this potential gravitational energy and the elastic energy of the spring given by equation \eqref{Pinball_energiaElastica}, we can then write the initial mechanical energy of the ball-spring system as

\begin{equation}

E_{m_1} = \frac{1}{2} kx^2 + mgd_1 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

So equation \eqref{Pinball_conservacion} becomes

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_conservacion2}

\frac{1}{2} kx^2 + mgd_1 \sin \theta = E_{m_2}.

\end{equation}

Let’s focus now on \(E_{m_2}\). They tell us that the ball barely makes it to the top of the board, which means that at that point the ball has no speed and so no kinetic energy. However, the ball has gravitational potential energy given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_potencial2}

U_{g_2} = mg h_2,

\end{equation}

where \(h_2\) is the height with respect to the reference point we used before. Again, it is easy to relate this height to the initial angle and the length of the board, as indicated in the diagram shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Ball’s position when reaching the top of the board. The distance along the board is denoted by \(d_2\) and its height by \(h_2\).

From this drawing, it is clear that

\begin{equation}

h_2 = d_2 \sin \theta,

\end{equation}

where we called \(d_2\) the length, which is one meter. Using this in \eqref{Pinball_potencial2} we get

\begin{equation}

U_{g_2} = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

When the ball is at the top of the board, the spring is no longer contracted, and so it has no elastic energy. This means that at the top of the board, the total mechanical energy of the ball-spring system is just the mechanical energy of the ball:

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_energia2}

E_{m_2} = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Insert this result in equation \eqref{Pinball_conservacion2} to get

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} kx^2 + mgd_1 \sin \theta = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Notice that we know all the variables here, except for \(k\), so we can use this equation to find the spring constant. First, leave the \(\frac{1}{2}kx^2\) term on the left side alone:

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} kx^2 = mg d_2 \sin \theta – mgd_1 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Now take common factor of \(mg\sin \theta \) on the right hand side to get

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} kx^2 = mg \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1).

\end{equation}

Now multiply by 2 and divide by \(x^2\) to get

\begin{equation}

k = \frac{2mg \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1)}{x^2}.

\end{equation}

Finally, insert the numerical values taking care of using the right units. In particular, we use that \(d_1= 1\, \text{cm}\) is the same as 0.01 meters, and 80 grams is the same as 0.08 kilograms. Then we get

\begin{equation}

k = \frac{2(0.08\, \text{kg})(9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2) \sin (6.5^\circ) ((1 \, \text{m}) – (0.01 \, \text{m}))}{(0.1 \, \text{m})^2},

\end{equation}

and the result is

\begin{equation}

k = 17.57 \, \text{N/m}.

\end{equation}

We also have to find the speed of the ball when it leaves the spring. To do this, we can use conservation of energy again. The energy at that point (that we can call \(E_{m_3}\)) must be the same as the energy at moment 1 or moment 2 from equation \eqref{Pinball_conservacion}. Let’s choose \(E_{m_2}\) since it is a bit simpler (but the reader can choose \(E_{m_1}\) if she wants to):

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_conservacion3con2}

E_{m_3} = E_{m_2}.

\end{equation}

We already know \(E_{m_2}\) from equation \eqref{Pinball_energia2}, so we can write

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_energia3}

E_{m_3} = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Let’s focus then on \(E_{m_3}\). At the point where the ball leaves the spring, the ball has some kinetic energy, given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_cinectica3}

K = \frac{1}{2} mv^2,

\end{equation}

where \(v\) is precisely the speed we need to find. At that moment, the ball also has some gravitational potential energy given by

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_potencial3}

U_{g_3} = mgh_3,

\end{equation}

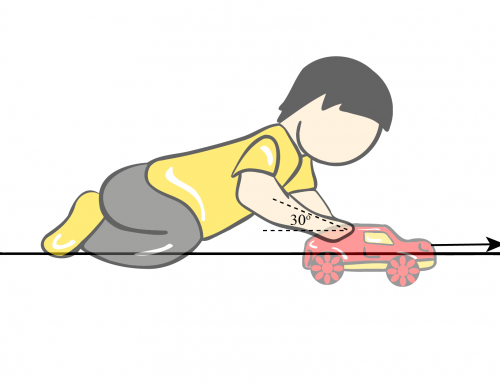

where \(h_3\) is the height at that point with respect to the bottom edge, as illustrated in figure 4.

Figure 4: Ball’s position as it leaves the spring. The distance along the board is denoted by \(d_3\) and the height by \(h_3\).

From the diagram, we see that

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_altura3}

h_3 = d_3 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Now, we can easily find \(d_3\), because we know the contraction of the spring and we also know \(d_1\). In particular, consider the diagram shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Spring’s contraction \(x\) illustrated in term of the distances \(d_1\) and \(d_3\). Recall that \(d_3\) is the distance at which the ball leaves the spring.

Clearly,

\begin{equation}

d_3 = d_1 + x.

\end{equation}

Hence, equation \eqref{Pinball_altura3} becomes

\begin{equation}

h_3 = (d_1 + x) \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Use this now in \eqref{Pinball_potencial3} to get

\begin{equation}

\label{Pinball_potencial3′}

U_{g_3} = mg(d_1 + x) \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Regarding the spring, at that moment the spring is no longer contracted, and so it has no elastic energy. So the total mechanical energy of the ball-spring system at moment 3 is just the kinetic energy of the ball (given by equation \eqref{Pinball_cinectica3}) and the gravitaitonal potential energy (given by equation \eqref{Pinball_potencial3′}). Using this in equation \eqref{Pinball_energia3}, we get

\begin{equation}

mg(d_1 + x) \sin \theta + \frac{1}{2} mv^2 = mg d_2 \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Leave now the \( \frac{1}{2} mv^2 \) alone on the left side:

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} mv^2 = mg d_2 \sin \theta – mg(d_1 + x) \sin \theta.

\end{equation}

Cancel the mass everywhere:

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} v^2 = g d_2 \sin \theta – g(d_1 + x) \sin \theta

\end{equation}

Take common factor of \(g \sin \theta \) on the right

\begin{equation}

\frac{1}{2} v^2 = g \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1 – x).

\end{equation}

Now multiply by 2:

\begin{equation}

v^2 = 2 g \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1 – x).

\end{equation}

Then, take the square root of this expression, to get

\begin{equation}

v = \sqrt{2 g \sin \theta (d_2 – d_1 – x)}.

\end{equation}

Finally, insert the numerical values using, again, the correct units:

\begin{equation}

v = \sqrt{2 (9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2) \sin (6.5^\circ) ((1 \, \text{m}) – (0.01 \, \text{m}) – (0.1 \, \text{m}))}.

\end{equation}

The result is

\begin{equation}

v = 1.4 \, \text{m/s}.

\end{equation}

Leave A Comment