An infinite plane generates a uniform electric field of magnitude \(E = 80 \, \text{N/C} \,\) 3 m away from itself.

a) What is the magnitude of the electric field if the distance from the plane is doubled?

b) What is the magnitude of the electric field if the distance from the plane is halved?

a) Use Gauss’s Law and calculate the distance.

b) Same hint as part (a).

Gauss’s Law states:

\begin{equation*}

\oint_S \vec{E}\cdot d\vec{A}=\frac{Q_{\text{enc}}}{\epsilon_0},

\end{equation*}

where we need to draw a cylinder as a Gaussian surface. Since the cylinder has two circular surfaces parallel to the plane, then a \(2\) must be multiplied by the electric field and the area. In this case, \(Q_{\text{enc}} = \sigma A\). Then:

\begin{equation*}

2EA=\frac{\sigma A }{\epsilon_0},

\end{equation*}

which can be rewritten as:

\begin{equation*}

E=\frac{\sigma }{ 2 \epsilon_0}.

\end{equation*}

Notice there is \({no}\) dependence on the distance \(h\).

(a) The electric field is \(E=80\,\text{N/C}\).

(b) The electric field is \(E=80\,\text{N/C}\).

For a more detailed explanation of any of these steps, click on “Detailed Solution”.

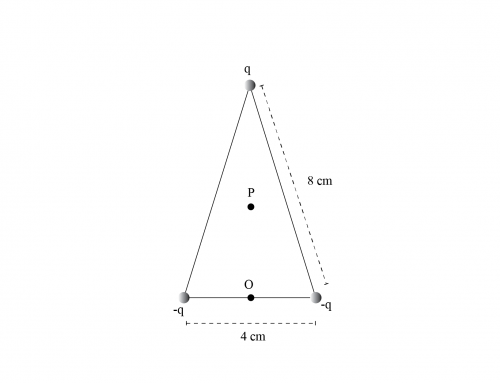

We need to find the electric field produced by an infinite plane at double and half the initial distance given. To answer both parts of the problem, we must first find a general expression for the electric field of an infinite plane at an arbitrary distance. In order to find this electric field, we must use Gauss’ law and the symmetry of the field emerging from the plane. We’ll suppose the infinite plane has a surface charge density \(\sigma\) and is located in the XY plane at \(z=0\). The electric field \(\vec{E}\) is directed in the Z axis emerging from the plane (assuming \(\sigma>0\)). For \(z>0\), the electric field is directed in the positive Z axis, and for \(z<0\) the electric field is directed in the negative Z axis. For the Gaussian surface, we choose a cylinder with area \(A\) in its base and total height \(2h\), as can be seen in figure 1.

Figure 1: Infinitely charged plane (grey) along the XY plane and its electric field \(\vec{E}\) along the positive and negative Z-axis. The cylindrical Gaussian surface (gold) is also shown with its transverse area \(A\) and total height \(2h\).

Now, we can write Gauss’ law

\begin{equation} \label{gausslaw} \oint_S \vec{E}\cdot d\vec{A}=\frac{Q_{\text{enc}}}{\epsilon_0}, \end{equation}

where the flux integral is performed over the closed surface \(S\), \(Q_{\text{enc}}\) is the charge enclosed by surface \(S\) and \(\epsilon_0\) is a physical constant known as the permitivity of free space. The vector \(d\vec{A}\) is a vector whose magnitude is the surface differential \(dA\) and its direction is perpendicular to the surface area always from the inside to the outside of the surface by convention. We divide the integral given on equation \eqref{gausslaw} into three integrals over three different surfaces. The surfaces will be: the circular surface on top \(S_1\) (\(z>0\)), the circular surface on the bottom \(S_2\) (\(z<0\)), and the curve surface that connects the top and bottom circular surfaces \(S_3\). Then, we can decompose the left-hand side of equation \eqref{gausslaw} as

\begin{equation}

\label{integral}

\oint_S\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{A}=\int_{S_1}\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1+\int_{S_2}\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2+\int_{S_3}\vec{E}_3\cdot d\vec{A}_3,

\end{equation}

where, for each integral, we must choose the appropriate vector \(d\vec{A}\) and electric field \(\vec{E}\) according to each surface.

First, let’s analyze the integral over the surface \(S_3\). The vector \(d\vec{A}\) in each point is different; however, in all point of surface \(S_3\) the vector is directed in the XY plane. Since the electric field is always directed in the Z axis (positive or negative), the vectors \(\vec{E_3}\) and \(d\vec{A}_3\) are perpendicular for all points on the surface \(S_3\); therefore, the dot product between these vectors is always zero; namely,

\begin{equation}

\vec{E}_3\cdot d\vec{A}_3=0.

\end{equation}

As a consequence, we have

\begin{equation}

\label{res3}

\int_{S_3}\vec{E}_3\cdot d\vec{A}_3=0.

\end{equation}

Now, let’s examine the integral \(\int_{S_1}\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1\). In this region, the electric field can be written as

\begin{equation}

\vec{E_1}=E\,\hat{\textbf{k}},

\end{equation}

where \(E\) is the magnitude of the electric field at a distance \(h\) from the plane, as shown in the first figure. The vector \(d\vec{A}_1\) is perpendicular to the circular area of the top of the cylinder, so

\begin{equation}

d\vec{A}_1=dA_1\,\hat{\textbf{k}}.

\end{equation}

Making the dot product between electric field and area vector, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\label{dot1}

\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1=(E\,\hat{\textbf{k}})\cdot(dA_1\,\hat{\textbf{k}})=EdA_a\,\hat{\textbf{k}}\cdot \hat{\textbf{k}}=EdA_1,

\end{equation}

where we used the fact that \(\hat{\textbf{k}}\cdot \hat{\textbf{k}}=1\). Using the result of equation \eqref{dot1} to calculate the integral \(\int_{S_1}\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1\), we get

\begin{equation}

\int_{S_1}\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1=\int_{S_1}E dA_1.

\end{equation}

We can take out the magnitude of the electric field \(E\) out of the integral because it is constant. Then, we end up with the result

\begin{equation}

E\int_{S_1}dA_1=EA,

\end{equation}

where in the last equality we performed the integral \(\int_{S_1}dA_1=A\), which is the area of the top circular surface. Thus,

\begin{equation}

\label{res1}

\int_{S_1}\vec{E}_1\cdot d\vec{A}_1=EA.

\end{equation}

Now, we’ll follow a similar procedure to calculate integral \(\int_{S_2}\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2\). First, in the region where \(S_2\) is located, the electric field is directed in the negative direction of the Z axis; so,

\begin{equation}

\label{e2}

\vec{E}_2=-E\,\hat{\textbf{k}}.

\end{equation}

where \(E\) is the magnitude of the electric field at a distance \(h\) from the infinite plane. For the vector \(d\vec{A}_2\), we can write

\begin{equation}

\label{da2}

d\vec{A}_2=-dA_2\,\hat{\textbf{k}}.

\end{equation}

The vector \(d\vec{A}_2\) is directed towards the negative direction of the Z axis because it is perpendicular to the surface \(S_2\) and directed from the inside of the surface towards the outside.

Using equations \eqref{e2} and \eqref{da2}, we can perform the dot product

\begin{equation}

\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2=(-E\,\hat{\textbf{k}})\cdot(-dA_2\,\hat{\textbf{k}})=EdA_2\,\hat{\textbf{k}}\cdot \hat{\textbf{k}},

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

\label{dot2}

\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2=EdA_2,

\end{equation}

where, in the last line, we used the fact that \(\hat{\textbf{k}}\cdot\hat{\textbf{k}}=1\).

Using the result of equation \eqref{dot2} to calculate the integral \(\int_{S_2}\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2\), we get

\begin{equation}

\int_{S_2}\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2=\int_{S_2}E dA_2.

\end{equation}

We can take the magnitude of the electric field \(E\) out of the integral because it is constant, so we end up with the result

\begin{equation}

E\int_{S_2}dA_2=EA,

\end{equation}

where in the last equality, we performed the integral \(\int_{S_2}dA_2=A\), which is the area of the bottom circular surface; thus,

\begin{equation}

\label{res2}

\int_{S_2}\vec{E}_2\cdot d\vec{A}_2=EA.

\end{equation}

Putting the results from equations \eqref{res3}, \eqref{res1}, and \eqref{res2} into equation \eqref{integral}, we obtain

\begin{equation}

\label{oint}

\oint_S\vec{E}\cdot d\vec{A}=EA+EA+0=2EA.

\end{equation}

Now, we turn our attention calculating the right-hand side of equation \eqref{gausslaw}, particularly the term \(Q_{\text{enc}}\). In terms of the surface charge density \(\sigma\), we can write the enclosed charge as

\begin{equation}

\label{qenc}

Q_{\text{enc}}=\int \sigma dA.

\end{equation}

Because the surface charge density is constant, we can take it out of the integral in equation \eqref{qenc} to obtain

\begin{equation}

Q_{\text{enc}}=\sigma\int dA.

\end{equation}

Performing the integral above, we get

\begin{equation}

\label{qenc2}

Q_{\text{enc}}=\sigma A,

\end{equation}

where \(A\) is the transverse area of the Gaussian surface, the one enclosing the infinite plane section.

Putting the results of equations \eqref{oint} and \eqref{qenc2} into equation \eqref{gausslaw}, we get

\begin{equation}

2EA=\frac{\sigma A}{\epsilon_0}.

\end{equation}

Cancelling out the area \(A\) and solving for \(E\), we have

\begin{equation}

E=\frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0}.

\end{equation}

Notice that the magnitude of the electric field \(E\) does not depend on \(h\), the distance from the infinite plane. It only depends on the surface charge density \(\sigma\) and \(\epsilon_0\), both of which are constants; thus, when the distance is changed, the magnitude of the electric field does not change. Hence,

(a) The electric field is \(E=80\,\text{N/C}\).

(b) The electric field is \(E=80\,\text{N/C}\).

Leave A Comment